Abstract

Background

Large clinical trials have emphasized that blood pressure control provides a major clinical benefit in reducing the risk of blindness in patients with diabetic retinopathy.

Methods

This audit was carried out to assess the quality of care for hypertension in 100 consecutive type II diabetics with diabetic retinopathy.

Results

The target blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg was achieved only in 38% of the patients. We also observed that 65% of the patients requiring diabetic macular laser treatment in this cohort had suboptimal control. The factors associated with suboptimal blood pressure control are identified and discussed.

Conclusion

Despite the unequivocal fact that lowering BP significantly reduces morbidity and mortality in diabetics, the majority of patients are not treated to a goal BP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy is a leading cause of blindness. Approximately 60% of adults with type II diabetes have comorbid hypertension (HT).1, 2 Most clinical trials uphold stringent target levels for blood pressure (BP) control in patients with diabetes as it significantly reduces the risk of cardiovascular and microvascular complications.3, 4 Aggressive BP control in diabetic retinopathy, in particular maculopathy provide a major clinical benefit in reducing the risk of blindness.

In this audit, we aimed to assess the quality of hypertension care in patients with type II diabetes with diabetic retinopathy and to identify factors associated with suboptimal care.

Methods

A total of 100 consecutive type II diabetics, who attended a diabetic eye clinic had their BP measured according to British Hypertensive Society guidelines.5 Patients were seated for 5 min and measurements were carried out twice with a 2-min rest between each by using a validated oscillometric digital monitor (OMRON 705 HEM CP; OMRON Healthcare, West Sussex, UK). The second reading was recorded and used in the analysis.

In addition, each patient answered a 7-item questionnaire on their BP monitoring. They included frequency of BP monitoring and who monitors it. The treatment regimes for hypertension, if any, were also recorded. The use of statins and aspirin were also noted. Ocular examination included visual acuity, the grade of diabetic retinopathy and the presence of active maculopathy or whether the patient had laser treatment for maculopathy in the last year.

The type of diabetes was classified as type II noninsulin controlled (diet-controlled or on oral hypoglycaemic agents) and type II insulin controlled. The target BP aimed was <140/80 as defined by the NICE guidelines.6 Patients were defined as hypertensive if their BP was above 140/80 or if they were on antihypertensives. The BP was defined as suboptimal control if it was >140/80 with or without treatment. If the systolic and diastolic blood pressure fell into two different groups, the diastolic BP was used to categorize them.

The results were recorded on a database and analysed.

Results

Table 1 gives the demographic details of the patients in this study. The majority of the patients (65%) were between 61 and 80 years of age.

The target BP of below 140/80 was achieved in 38 patients (38%) with or without treatment. Of these, 70% were on antihypertensives. Of the patients on antihypertensive medications, only 25/70 (36%) met the target BP.

The BP was monitored by the nurses at the GP practice or at the hospital diabetic service. 11% self-monitored their BP and kept a record of it.

Frequency of monitoring BP is shown in Table 2.

Of the 39% that were monitored at <6 months intervals, 64% were monitored at the hospital diabetic centre. In all, 22% did not have their BP monitored at least annually. In this group, 82% (18/22) had BP over 141/81, and 36% (8/22) had BP >161/101.

Patients who visited the diabetic hospital service were better controlled than those at the general practice. This also related to the fact that all insulin-dependent diabetics were under the care of the hospital diabetic service while most noninsulin-dependent were under the care of general practitioners.

Table 3 shows that the control of BP was less effective in patients on less than two antihypertensive agents.

In all, 28% of the patients were on statins while 26% took aspirin daily. The need for laser was correlated to the hypertensive control in these patients. The retinopathy status is shown in Table 4.

In all, 65% of the diabetic macular laser performed in the last year in this cohort was on patients with suboptimal BP control.

Discussion

The risk of diabetic retinopathy in type II diabetics is strongly associated with higher blood pressure. The UKPDS showed that tight blood pressure control in patients with hypertension and type II diabetes achieved a 34% reduction in the rate of progression of retinopathy.3 In addition, blood pressure control led to a 47% reduction in visual function as measured on a standardized vision test suggesting that tight blood pressure control also prevented the development of diabetic maculopathy, which is the main cause of visual impairment in type II diabetes.7 As diabetic maculopathy responds less well to laser retinal photocoagulation than proliferative retinopathy,8 reducing the risk of maculopathy by tight blood pressure control might provide a major clinical benefit in reducing the risk of blindness.

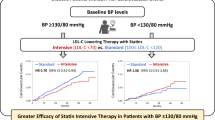

The standard for this audit was a blood pressure of ≤140/80 mmHg. Our analysis showed that only 38% reached the ≤140/80 mmHg goal, of whom only 53% received multiple drug regime. These data suggest that though the goal appears to be too strict, there is room for more aggressive measures of lowering BP in diabetics. Physicians and primary care doctors should increase their threshold to accept blood pressure outside national guidelines and be keen to change or initiate treatment. In fact, the UKPDS 38 showed that for each 10-mmHg decrease in mean systolic blood pressure, there was a 13% reduction in the risk of diabetic retinopathy. The clear benefit demands that more aggressive measures be taken for optimal control of BP.

This audit also showed that 65% of patients needing laser treatment for diabetic maculopathy had suboptimal diabetic control. The UKPDS study showed that there was a decrease in the need for laser in patients with tight control.3 This is further substantiated by the HOPE trial that showed Ramipril group showed a nonsignificant trend toward less laser therapy for retinopathy. One of the most striking observations from the HOPE trial is that relatively large reductions in risk were achieved in the face of comparatively small reductions in blood pressure.4 Approximately 29% of patients having a 20-year or more duration of diabetes will exhibit macular oedema, with over 50% experiencing a loss of two or more lines of vision after 2 years of follow-up.9 Even a small reduction in incidence by improved blood pressure control would yield substantial visual benefit and cost savings.10

Other aspects of suboptimal care included inefficient monitoring of blood pressure. Only 39% of the patients in this study had their blood pressure checked in the last 6 months. This may be attributed to workload and lack of resources to organize regular follow-up.11, 12 With the current model of health care, the attainment of these targets seem to be difficult in the majority of diabetic cases. Nurse-led clinics is an effective strategy in the intensification of BP monitoring and management for type II diabetics.13 Another option is self-monitoring of BP and maintaining a log to review blood pressure. At present, this is not as popular as the log for blood glucose levels. Only 11% of this cohort monitored their BP at home. Attendance at the diabetic eye clinic is also an important chance to detect both new patients with systemic hypertension and those with inadequate BP control. This audit emphasizes the fact that ophthalmologists should be encouraged to measure BP in their diabetic patients attending diabetic eye clinics.14

Blood pressure was better controlled in insulin-dependent diabetics than noninsulin-dependent cases. This may be because insulin-dependent patients are monitored by the hospital diabetic service and are monitored more closely. While intensification of glycaemic control can initially worsen the diabetic retinopathy, the aggressive control of BP at this stage will definitely help to reduce risk of worsening of diabetic retinopathy.

It should be borne in mind that hypertension in diabetes is more difficult to control, despite being more likely to receive enhanced benefit from effective management. A review of recently completed clinical trials indicates that >65% of people with diabetes and hypertension will require ≥2 different antihypertensive medications to achieve the new suggested target blood pressure of <130/85 mmHg.4, 15 In all, 9% of this study group had three or more antihypertensive drugs and were still uncontrolled despite being monitored <6 monthly.

Not all obstacles are induced by the health care system. Patients need to play a key role in the management as well. Patient factors include lack of knowledge about the risks of uncontrolled hypertension, poor compliance, loss of follow-up and cost of treatment. We did not formally assess compliance or patient education in this study but the reinforcement of patient education positively affects blood pressure control. The doctors in the diabetic eye clinics should emphasize the need of tight BP control, give nonpharmacologic advice on healthy living and advise smokers to stop smoking.

Conclusion

Despite the unequivocal fact that lowering BP below 140/80 mmHg significantly reduces morbidity and mortality, the majority of patients are not treated to a goal BP. Despite the difficulty in achieving goal in these patients, physicians should not waiver in their resolve to treat these patients aggressively, because these high-risk individuals are the most likely to receive enhanced benefit from effective management. Clinicians in primary care settings should be well positioned to participate in the prevention and management of visual disability. They can have a significant impact on their patients' visual health by aggressively controlling known risk factors for visual loss.

References

Chamontin B, Poggi L, Lang T, Menard J, Chevalier H, Gallois H et al. Prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension in the French population: data from a survey on high blood pressure in general practice, 1994. Am J Hypertens 1998; 11: 759–762.

Marques-Vidal P, Tuomilehto J . Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in the community: Is the ‘rule of halves’ still valid? J Hum Hypertens 1997; 11: 213–220.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998; 317: 703–713.

Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, et al., for the HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood pressure-lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomized trial. Lancet 1998; 351: 1755–1762.

Ramsay LE, Williams B, Johnston GD, MacGregor GA, Poston L, Potter JF et al. Guidelines for management of Hypertension: report of the Third Working Party of the British Hypertension Society, 1999. J Hum Hypertens 1999; 13: 569–592.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. BMJ 1998; 317: 713–720.

Davies EG, Petty RG, Kohner EM . Long term effectiveness of photocoagulation for diabetic maculopathy. Eye 1989; 3: 764–767.

Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BE, Davis MD, DeMets DL . The wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy XI the incidence of macular edema. Ophthalmology 1989; 96: 1501–1510.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Cost effectiveness analysis of improved blood pressure control in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 40. BMJ 1998; 317(7160): 720–726.

Schaars CF, Denig P, Kasje WN, Stewart RE, Wolffenbuttel B, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM . Physician, organizational, and patient factors associated with suboptimal blood pressure management in type 2 diabetic patients in primary care. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(1): 123–128.

Denig P, Schaars CF, Kasje WN, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM . Patient, doctor, and organisational factors affecting hypertension management in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 57(3): 357.

Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Austin AA, Cappuccio F . Is there a role for nurse-led blood pressure management in primary care? Family Practice 2003; 20(4): 469–473.

Al-Husainy S, Farmer J, Gibson JM, Dodson PM . Is measurement of blood pressure worthwhile in the diabetic eye clinic? Eye 2005; 19(3): 312–316.

Moser M . Current recommendations for the treatment of hypertension: are they still valid? J Hypertens Suppl 2002; 20(1): S3–S10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

None of the authors have any financial interest in this project

This audit was presented as a poster in the Oxford Ophthalmological Congress, July 2005

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sivaprasad, S., Jackson, H. Blood pressure control in type II diabetics with diabetic retinopathy. Eye 21, 708–711 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702307

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702307

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Optimizing Medical Management in Patients with Sight-Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy

Ophthalmology and Therapy (2017)

-

High HbA1c level was the most important factor associated with prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Taiwanese type II diabetic patients with a fixed duration

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2013)

-

A mitochondria-localized glutamic acid-rich protein (MGARP/OSAP) is highly expressed in retina that exhibits a large area of intrinsic disorder

Molecular Biology Reports (2011)

-

Spironolactone for poorly controlled hypertension in type 2 diabetes: conflicting effects on blood pressure, endothelial function, glycaemic control and hormonal profiles

Diabetologia (2008)

-

The relevance of blood pressure measurements in patients attending a diabetic eye clinic: the use of an electronic patient record

Eye (2007)