Abstract

Introduction

Premix insulin analogs are a well-established treatment for type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, there is a lack of simple, clear guidance on some aspects of their use. These include choosing a regimen for insulin initiation, recognizing when patients need intensification of therapy, and switching from basal–bolus to a premix insulin analog when appropriate.

Methods

An independent expert panel formulated recommendations on the use in T2D of the premix insulin analog formulations widely available in Australasia, based on the available evidence and their own experience.

Results

Results from trials in both initiation and intensification of insulin show that no single insulin or regimen is best on all endpoints, and that improved glycemic control can be expected regardless of which regimen is used. Thus, individual patient factors and preferences become more important. Guidance is presented to help the clinician choose between a premix insulin analog or basal analog for insulin initiation, and to intensify insulin therapy using premix insulin analogs. Recommendations are made on dosing, titration, the concomitant use of non-insulin glucose-lowering drugs, and other practical issues, and on the special case of switching from basal–bolus to premix insulin analog therapy.

Conclusion

This guidance is intended to help both general and specialist practitioners make informed choices and provide optimal care for patients with T2D. It emphasizes the importance of taking into account individual patient factors and preferences so that the choice of insulin regimen is individualized to the patient in the same way that glycemic targets are now individualized.

Funding

Novo Nordisk Region IO A/S.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Premix insulin analogs are well established as a treatment for type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, there is a lack of clear practical guidance to help clinicians choose an initial regimen. A number of overarching criteria need to be taken into consideration. These include the need to target both fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and postprandial glucose (PPG) to achieve optimal glycemic control [1]; the importance of individualizing therapy; and the need to intensify the insulin regimen to compensate for the progressive nature of diabetes. Furthermore, currently available literature contains almost no information on how to switch patients from basal–bolus to premix therapy when patients fail to cope with the more intensive insulin regimen. With the growing prevalence of T2D, the responsibility for the care of patients is increasingly moving to general practitioners (GPs), many of whom would welcome clear and straightforward guidance on insulin management.

With this in mind, the authors of this report—an independent expert panel of endocrinologists and GPs with a special interest in diabetes, all based in Australia and New Zealand—met in Sydney in February 2014. The panel’s objective was to formulate guidance on how to undertake the following activities: initiating therapy with premix insulin analogs; recognizing when patients need intensification of their insulin therapy; and switching from basal–bolus to premix insulin analog therapy when appropriate.

Methods

The panel chose to focus on the premix insulin analog formulations widely available in Australasia as of February 2014: biphasic insulin aspart, containing 30% soluble insulin aspart and 70% protamine-crystallized insulin aspart (BIAsp 30), and biphasic insulin lispro, containing 25% soluble insulin lispro and 75% protamine-crystallized insulin lispro (lispro mix 25). In this document, the term ‘premix insulin analogs’ covers both BIAsp 30 and lispro mix 25; the term ‘premix insulins’ is used to cover both human and analog premixes when citing references where the term was used in this way.

The panel’s intention is that the guidance should be specific and detailed enough to be useful in primary care as well as for specialists. As far as possible, the recommendations are evidence based. However, since the evidence on approaches for treatment is incomplete, some of the recommendations are given by the writing group as a consensus and indicated as such.

The guidance in this statement covers T2D only and does not include type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes, latent autoimmune diabetes of adults, patients in end-stage renal disease, or steroid-induced diabetes. The recommendations have been formulated for Australia and New Zealand, but should be useful globally. No representations are made about local prescribing regulations or funding status in specific countries. Currently, evidence is not available to make recommendations concerning new combination insulins, such as insulin degludec/insulin aspart, or other new combination regimens such as insulin–incretin combinations. This guidance will, therefore, be subject to change as new information becomes available.

It should be noted that the guidance provides recommendations that are intended to be helpful, and that none of the suggested actions are mandatory.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Current Guidelines

Previously, guidelines on the management of T2D prescribed fixed glycemic targets for all patients. More recent guidance from bodies such as the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) have formalized the concept of ‘patient-centered care’, which includes setting targets in line with individual patients’ needs, preferences, and tolerances [2, 3]. This concept is now increasingly accepted. Glycemic targets that will be appropriate for most patients are still suggested, as shown in Table 1, but with the understanding that individualization of targets is imperative.

Choosing an appropriate insulin type and regimen should also be based on specific patient attributes [5], rather than taking a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, and many guidelines now recognize both basal and premix insulin as options for initiating/intensifying insulin therapy in T2D (Table 1). Indeed, the loss of the first-phase insulin release is one of the earliest detectable defects of beta-cell function in individuals destined to develop T2D [9]. The resultant postprandial hyperglycemia has been associated with an increased risk of harmful outcomes such as macrovascular disease, retinopathy, and cancer [1]. Unlike basal insulin, premix insulin targets both FPG and PPG, which is essential for addressing this glycemic defect and achieving optimal glycemic control. With this in mind, it is important to determine the glycemic defect through blood glucose monitoring before choosing an insulin initiation regimen.

It is important to note that the ADA/EASD statement emphasizes the progressive nature of T2D and the likelihood that intensification of therapy will be needed as beta-cell function deteriorates [2].

Evidence Base for Premix Insulin Analogs in Initiation, Intensification, and Switching

Initiation of Insulin: Premix Insulin Analogs Vs. Basal Analogs

An extensive clinical dataset, based on numerous randomized clinical trials and real-life observational studies, supports the efficacy and good safety profiles of BIAsp 30 and lispro mix 25 in the initiation and intensification of insulin therapy; these data have been reviewed [10, 11].

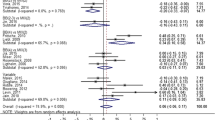

A small number of trials compared the use of either premix insulin analogs or basal insulin analogs for insulin initiation. Systematic reviews of the available evidence [12–14] suggest that treatment with premix insulin analogs as first-line insulin therapy results in significantly better overall glycemic control, but slightly greater risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain, compared with basal insulin. A more recent review of eight trials comparing insulin initiation with either premix analogs or basal analogs showed greater glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) reductions, weight gain, and number of hypoglycemic episodes with the premix analogs (significance of differences not reported) [15]. The authors suggested that factors that are not addressed in clinical trials, such as complexity of regimens and the need for titration, may influence outcomes.

The most recently published trial comparing BIAsp 30 once daily (OD) with a basal analog (insulin glargine OD) for insulin initiation in T2D was OnceMix (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00469092) [16]. The estimated mean reduction in HbA1c was −1.41% (15 mmol/mol) with BIAsp 30 and −1.25% (14 mmol/mol) with insulin glargine (difference [95% confidence interval]: −0.16% [−0.30; −0.02] or −2 mmol/mol [−3; −0.2]; P = 0.029). There was a significant improvement in PPG with BIAsp 30 after dinner and before bed when compared with insulin glargine, with differences of −0.52 mmol/L (P = 0.04) and −0.78 mmol/L (P < 0.01), respectively. The risk of hypoglycemia, while low in both groups, was slightly higher with BIAsp 30 for overall hypoglycemia (6.5 vs. 4.8 episodes/patient-year; P = 0.034) and nocturnal hypoglycemia (1.1 vs. 0.5 episodes/patient-year; P = 0.003). However, the proportion of patients who achieved an HbA1c level <7% with no hypoglycemia was the same in the two groups (20.0% with BIAsp 30 and 19.4% with insulin glargine). Weight change did not differ between the groups.

DURABLE (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00279201) compared lispro mix 25 twice daily (BID) with insulin glargine OD in previously insulin-naïve patients [17]. Treatment with lispro mix 25 resulted in slightly greater reductions in HbA1c at 24 weeks: −1.8 ± 1.3% (−20 ± 14 mmol/mol) vs. −1.7 ± 1.3% (−19 ± 14 mmol/mol) (P = 0.005). The lispro mix group also had more weight gain: 3.6 ± 4.0 vs. 2.5 ± 4.0 kg (P < 0.0001) and higher rates of overall hypoglycemia (28.0 ± 41.6 vs. 23.1 ± 40.7 episodes/patient-year; P = 0.007), but lower rates of nocturnal hypoglycemia (8.9 ± 19.3 vs. 11.4 ± 25.3 episodes/patient-year; P = 0.009). A follow-up study over 24 months showed durability of glycemic control was longer with lispro mix 25 [18].

Intensification of Insulin: Premix Insulin Analogs vs. Basal-Plus or Basal–Bolus Regimens

A meta-analysis published in 2011 [19] compared premix insulin analogs with basal–bolus therapy based on three trials: PREFER (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00605020), which compared BIAsp 30 BID with insulin detemir plus insulin aspart at mealtimes [20]; a study comparing lispro mix 50 (containing 50% soluble insulin lispro and 50% protamine-crystallized insulin lispro) three times daily (TID) with insulin glargine plus insulin lispro TID [21]; and the 3-year follow-up of the 4T study, comparing BIAsp 30 BID, insulin aspart TID, or insulin detemir OD or BID as initial regimens [22]. In 4T, if glycemic control was inadequate, lunchtime insulin aspart was added to BIAsp 30 BID, bedtime basal insulin was added to insulin aspart TID, and insulin aspart TID was added to basal insulin. Most of the patients in the prandial and basal groups switched to basal–bolus therapy [23]. Based on these three trials, the authors concluded that patients treated with a basal–bolus regimen had a higher chance of reaching their HbA1c goal (odds ratio [95% confidence interval]: 1.75 [1.11; 2.77]), with no difference in incidence of hypoglycemia or weight gain between the two regimens [19]. The results have to be interpreted cautiously, as the trial populations included insulin-naïve patients as well as patients already receiving basal insulin at the start of the treatment periods.

Further studies have been published since 2011, some only as abstracts at the time of the panel meeting. In PARADIGM (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00548808), lispro mix 25 OD, BID, or TID, as needed, was compared with insulin glargine plus one, two, or three injections of insulin lispro, as needed. Glycemic control, weight change, hypoglycemia, the number of injections, and the increase in insulin dose were all similar between groups [24]. A phase IV study, GALAPAGOS (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01121835), compared BIAsp 30 OD or BID with insulin glargine OD plus insulin glulisine OD if needed (‘basal-plus’). With BIAsp 30, 52.6% of patients achieved HbA1c <7% compared with 43.2% of those receiving basal-plus (P = 0.005). However, rates of hypoglycemia were higher with BIAsp 30: 2.9 vs. 1.2 episodes/patient-year for overall hypoglycemia, and 1.0 vs. 0.4 episodes/patient-year for nocturnal episodes (both P < 0.01) [25]. Finally, the LanScape study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00965549) compared BIAsp 30 OD with insulin glargine OD plus insulin glulisine OD at the main meal [26]. Reduction in HbA1c did not differ between the two regimens. There was no difference between overall hypoglycemia rates, but there were fewer nocturnal events with BIAsp 30 OD (3.6 vs. 5.7 events/patient-year; P = 0.02).

Factors influencing the choice of either premix insulin analogs or basal–bolus regimens for intensification in a primary care setting have recently been reviewed [27]. The authors of this study found inconclusive evidence and a lack of direct comparisons, and pointed out that clinical trials do not necessarily reflect real-world patients. In their view, GPs know their patients well and are in a good position to select the appropriate regimen for their patients (e.g., premix or basal-plus/basal–bolus therapy). However, GPs need sufficient time and support to accomplish this task.

Switching from Basal–Bolus to Premix Therapy

Switching from a basal–bolus insulin regimen to premix insulin analogs is a relatively uncommon scenario. While basal–bolus therapy is considered the ‘gold standard’ for patients with advanced T2D, two groups of patients may need to switch to premix insulin analogs either BID or TID. These are patients who are unable or unwilling to cope with the complexity of a basal–bolus regimen, and patients who commence treatment with basal–bolus therapy in hospital (as occurs routinely in Australia, in accordance with guidelines from the Australian Diabetes Society [28]) and no longer require such an intensive regimen following discharge.

There is minimal published evidence on how to make this switch. Some evidence is available from a subgroup of the observational A1chieve study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00869908), in which patients who were inadequately controlled on antidiabetic medication started or were switched to either BIAsp 30, insulin aspart, or insulin detemir [29]. The subgroup consisted of patients who were inadequately controlled on basal–bolus therapy using insulin glargine (n = 240) or neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin (n = 784) and who switched to BIAsp 30, mostly BID [30]. At 24 weeks, mean HbA1c decreased by approximately 2.5% (27 mmol/mol) and 1.9% (21 mmol/mol), respectively (P < 0.001 in both groups). The proportions reporting overall, major, or nocturnal hypoglycemia were significantly reduced (P < 0.05 in all cohorts) after switching to BIAsp 30. While this was not a randomized trial, the results do suggest that selected patients inadequately controlled on a basal–bolus regimen can benefit by switching to a premix insulin analog. The authors speculate that the improved results may have arisen from better therapy adherence due to the simpler regimen with BIAsp 30.

To our knowledge, the only previously published recommendations for switching from basal–bolus therapy to premix insulin analogs were included in Turkish guidelines, not available in English, on the use of BIAsp 30 in T2D [31]. These suggested that patients should be switched to BIAsp 30 BID or TID in preference to OD.

Conclusions from the Available Evidence

The results from the trials in both initiation and intensification of insulin show that, in general, a better HbA1c reduction was accompanied by a higher rate of hypoglycemia, and both arms were accompanied by weight gain. No single insulin or regimen was best on all endpoints. Furthermore, while the differences may have reached statistical significance, they were often of limited clinical relevance. It is clear that improved glycemic control can be expected, irrespective of which regimen is used. Thus, individual patient factors and preferences become more important, and the focus must be on selecting the regimen that is best for the particular patient—including any features likely to aid adherence.

It is important to choose a regimen to which patients are likely to adhere. Non-adherence to insulin therapy has been linked with unfavorable outcomes [32, 33]; conversely, treatment persistence has been associated with improved clinical outcomes [34]. A full discussion of adherence issues is outside the scope of this guidance. However, studies of adherence to antidiabetic therapy in general (not necessarily insulin) have shown that factors affecting adherence include the patient’s comprehension of the treatment regimen and its benefits, adverse effects, medication costs, regimen complexity, and frequency and timing of dosing [35, 36]. One study showed that the main predictor of adherence was patients’ ratings of the burden of therapy, and that the patients’ perceived burden of therapy increased as the number of injections increased [37].

Very little evidence is available on the scenario in which patients need to switch from basal–bolus to premix insulin therapy.

Recommendations

Initiating Insulin Therapy with Premix Insulin Analogs in Primary Care

Preparing Patients for Insulin Therapy

Patients may fear initiating insulin for many reasons: fear of hypoglycemia or weight gain; concern that insulin therapy indicates that they are heading towards severe complications such as blindness, limb amputation, or kidney failure; resistance to the need for monitoring blood glucose; or a belief that starting insulin indicates a failure on their part. It is important to allay these fears [38, 39]. It is also important to select the right HbA1c target for the individual patients. If the target is set too low, patients may omit insulin to avoid hypoglycemia, at the expense of their glycemic control.

Choosing the Most Appropriate Insulin Regimen for the Patient

When choosing an insulin regimen for initiation, it is imperative to bear in mind the long-term progressive nature of T2D and the likely need for intensification. The patient’s ability to cope with intensification should influence the choice of initiation regimen.

Figure 1 summarizes patient characteristics that may help determine a preference for either basal insulin or premix insulin analogs. Choose the regimen that provides the best match overall to the characteristics described. Age is not shown in Fig. 1, as function and degree of frailty are more important than chronological age. If life expectancy is short, the probability of future insulin intensification is less important.

Patient factors to consider when deciding whether to use premix insulin analog or basal insulin for initiation (based on consensus). The figure shows both immediately applicable factors and other factors that will determine whether future intensification should be with basal–bolus or premix insulin analog therapy

Dosing, Titration, and Monitoring

See “Box 1” for guidance on dose and titration when initiating insulin with premix insulin analogs.

Use of Other Glucose-Lowering Drugs

See “Box 2” for guidance on the use of other glucose-lowering drugs when initiating insulin with premix insulin analogs.

Intensifying Insulin Therapy to Premix Insulin Analogs BID in Primary Care

This guidance covers intensification from premix insulin analogs OD or basal insulin only to premix insulin analogs BID. Other choices of intensification regimen are not covered here. For a review of the options for a second-line insulin regimen, see Barnett and colleagues [40].

When to Intensify

Intensification of insulin therapy is as important as initiation. Regular review with appropriate dose adjustment is critical, to ensure that the patient does not continue on their initiation regimen if glycemic control is suboptimal. Intensification is required if the individual’s HbA1c level remains above the individualized target for 3–6 months without any obvious reversible reason such as a steroid course or dietary non-compliance. Insulin should also be intensified if 2-h postprandial blood glucose values are above 10 mmol/L (180 mg/dL) and there is a difference (postmeal minus premeal) of ≥3 mmol/L (≥54 mg/dL), or when the maximum dose of 40–50 units is reached on premix insulin analog OD.

Practical Guidance for Switching

Practical guidance already exists for intensifying from basal insulin only or premix insulin analog OD to premix insulin analog BID [41]. “Box 3” and Figs. 2 and 3 have been adapted from this reference. For titration and monitoring when intensifying to premix insulin analog BID, refer to the guidance above on initiation (“Box 1”).

A simple algorithm for switching from basal insulin therapy OD or BID (analog or human) to BID premix insulin analog. Modified from [41]. BID twice daily, FPG fasting plasma glucose, OD once daily

A simple algorithm for intensifying premix insulin analog therapy from OD to BID. Modified from [41]. aThe evening meal is given as an example. Breakfast injections may also be suitable, in which case the pre-evening meal blood glucose should be monitored. bSplit the OD dose 50/50 breakfast and dinner. BID twice daily, FPG fasting plasma glucose, OD once daily

Further Intensification for Patients Already on Premix Insulin Analog BID

Use of premix insulin analogs TID may be needed owing to poor control, but this regimen is used much less often than premix insulin analogs OD or BID. In the panel members’ experience, the move from two to three injections daily can represent a larger barrier to patients than the move from one to two injections; patients must also be willing to undertake sufficient self-testing. If control is not satisfactory using a premix insulin analog BID, consider referring the patient to a specialist; otherwise, refer to the existing practical guidance for intensification [41].

The ratio of short- to intermediate-acting insulin in both BIAsp 30 and lispro mix 25 will be appropriate for most patients. Different ratio premixes, such as 50% soluble rapid-acting insulin/50% protaminated insulin, are also available and can be useful for patients with specific needs (e.g., patients with very high PPG values or problems with hypoglycemia). For information on intensifying to higher ratio premix insulin analogs, refer to the published guidance [43].

Switching from Basal–Bolus to Premix Insulin Analog Therapy in Primary Care

Practical Guidance: Chronic Treatment Failure

Not all patients achieve successful glycemic control with long-term basal–bolus therapy. The reasons for this are many and, with further education, the regimen may prove to be appropriate. For others, switching to a premix insulin analog may be the right decision. For example, some patients are unwilling or unable to deal with complexity, or they may have tried a basal–bolus regimen but their circumstances may have changed. Others may find carbohydrate counting, dose adjustment, or the required degree of monitoring too difficult, or be unable to handle two different insulin delivery devices.

To date, there is limited published evidence concerning this change, although all practicing endocrinologists will have experience in this situation. Rather than suggesting a specific HbA1c cutoff for switching regimens, we suggest a switch to premix insulin analogs in patients who are clearly unable or unwilling to use basal–bolus therapy, or whose HbA1c has consistently remained above target despite using a basal–bolus regimen while having access to proper training and adequate information.

The default switch is to premix insulin analog BID, not TID, and the titration guidance shown in “Box 4” is our suggested approach. If the patient is transferring from an analog basal–bolus regimen, education concerning the need to resuspend the protaminated insulin is important.

Practical Guidance: Patients Discharged from Hospital

Some hospitalized patients may have been placed on a basal–bolus regimen to provide a flexibility of management that is not required following discharge. Under these circumstances, switching to an alternate premix insulin regimen would be appropriate.

In such patients, it is important to be conservative, and insulin requirements may change dramatically from those required in hospital. Discharge planning is vital and expert input is desirable. For titration guidelines, see “Box 4”.

Conclusions

The purpose of this document is to provide practical and simplified guidance on the use of premix insulin analogs for insulin initiation and intensification in patients with T2D.

A review of published studies clearly demonstrates that proper use of any insulin regimen will result in a reduction in HbA1c, but that the greater the improvement in glycemic control, the greater the risk of side effects. Thus, individual patient factors and preferences become more important. As such, the choice of insulin regimen should be individualized to the patient, in the same way that glycemic targets are now individualized.

A figure is provided to help clinicians choose between premix insulin analogs or basal insulin for insulin initiation (Fig. 1). Key to making this choice is the need to bear in mind the patient’s ability to cope with either a premix insulin analog or basal–bolus regimen when intensification of therapy is needed.

Guidance is provided on dosing, titration, the concomitant use of non-insulin glucose-lowering drugs, and other practical issues in both initiation and intensification. A titration algorithm is provided for the special case of switching from basal–bolus to premix insulin analog therapy (“Box 4”). In all situations, safety is key and insulin should be titrated slowly.

The expert panel hopes that these recommendations, and in particular the specific dose values and targets, will prove a useful resource for all clinicians as they seek to provide optimal care for their patients with T2D.

Notes

If HbA1c is above a certain point [we suggest ≥8.5% (≥70 mmol/mol)], it is also possible to initiate therapy with 6 units BID.

References

International Diabetes Federation. 2011 Guideline for management of postmeal glucose in diabetes. Available from: www.idf.org/2011-guideline-management-postmeal-glucose-diabetes. Accessed Sept 2014.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–79.

International Diabetes Federation. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. Available from: www.idf.org/global-guideline-type-2-diabetes-2012. Accessed Sept 2014.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–80.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2013 consensus statement. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(Suppl 2):1–48.

Colagiuri S, Dickinson S, Girgis S, Colagiuri R. National evidence based guideline for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes. Canberra: Diabetes Australia and the National Health and Medical Research Council; 2009.

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and Diabetes Australia. General practice management of type 2 diabetes—2014–15. Melbourne: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2014. Available from: http://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/PageFiles/763/UPdated%20GP%20guidelines.pdf. Accessed Sept 2014.

New Zealand Guidelines Group. Management of type 2 diabetes. In: New Zealand primary care handbook 2012. 3rd ed. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group; 2012. Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/nz-primary-care-handbook-2012.pdf. Accessed Sept 2014.

Polonsky KS, Given BD, Hirsch LJ, et al. Abnormal patterns of insulin secretion in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1231–9.

Liebl A, Prusty V, Valensi P, et al. Ten years of experience with biphasic insulin aspart 30. Drugs. 2012;30:1495–520.

Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Razzoli E, Esposito K. Defining the role of insulin lispro in the management of postprandial hyperglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Drug Investig. 2008;28:199–210.

Ilag LL, Kerr L, Malone JK, Tan MH. Prandial premixed insulin analogue regimens versus basal insulin analogue regimens in the management of type 2 diabetes: an evidence-based comparison. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1254–70.

Qayyum R, Bolen S, Maruthur N, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and safety of premixed insulin analogues in type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:549–59.

Lasserson DS, Glasziou P, Perera R, Holman RR, Farmer AJ. Optimal insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1990–2000.

Vaag A, Lund S. Insulin initiation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: treatment guidelines, clinical evidence and patterns of use of basal vs premixed insulin analogues. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:159–70.

Strojek K, Bebakar WM, Khutsoane DT, et al. Once-daily initiation with biphasic insulin aspart 30 versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with oral drugs: an open-label, multinational RCT. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2887–94.

Buse JB, Wolffenbuttel BH, Herman WH, et al. The DURAbility of Basal versus Lispro mix 75/25 insulin Efficacy (DURABLE) trial 24-week results: safety and efficacy of insulin lispro mix 75/25 versus insulin glargine added to oral antihyperglycemic drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1007–13.

Buse JB, Wolffenbuttel BH, Herman WH, et al. The DURAbility of Basal versus Lispro mix 75/25 insulin Efficacy (DURABLE) trial: comparing the durability of lispro mix 75/25 and glargine. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:249–55.

Giugliano D, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Chiodini P, Ceriello A, Esposito K. Efficacy of insulin analogs in achieving the hemoglobin A1c target of <7% in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:510–7.

Liebl A, Prager R, Binz K, et al. Comparison of insulin analogue regimens in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the PREFER Study: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:45–52.

Rosenstock J, Ahmann AJ, Colon G, Scism-Bacon J, Jiang H, Martin S. Advancing insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes previously treated with glargine plus oral agents: prandial premixed (insulin lispro protamine suspension/lispro) versus basal/bolus (glargine/lispro) therapy. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:20–5.

Holman RR, Thorne KI, Farmer AJ, et al. Addition of biphasic, prandial, or basal insulin to oral therapy in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1716–30.

Holman RR, Farmer AJ, Davies MJ, et al. Three-year efficacy of complex insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1736–47.

Bowering K, Reed VA, Felicio JS, Landry J, Ji L, Oliveira J. A study comparing insulin lispro mix 25 with glargine plus lispro therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycaemic control on oral anti-hyperglycaemic medication: results of the PARADIGM study. Diabet Med. 2012;29:e263–72.

Aschner P, Sethi B, Gomez-Peralta F, et al. Glargine vs. premixed insulin for management of type 2 diabetes patients failing oral antidiabetic drugs: the GALAPAGOS study. Diabetes. 2013;62(Suppl 1):A241–2.

Vora J, Cohen N, Evans M, Hockey A, Speight J, Whately-Smith C. Glycemic control and treatment satisfaction in type 2 diabetes: basal plus compared with biphasic insulin in the LANSCAPE trial. Diabetes. 2013;62(Suppl 1A):LB13.

Mosenzon O, Raz I. Intensification of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetic patients in primary care: basal–bolus regimen versus premix insulin analogs. When and for whom? Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 2):S212–8.

Australian Diabetes Society. Guidelines for routine glucose control in hospital. Sydney: Australian Diabetes Society; 2012. https://diabetessociety.com.au/documents/ADSGuidelinesforRoutineGlucoseControlinHospitalFinal2012_000.pdf. Accessed June 2015.

Home P, Naggar NE, Khamseh M, et al. An observational non-interventional study of people with diabetes beginning or changed to insulin analogue therapy in non-Western countries: the A1chieve study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:352–63.

Dieuzeide G, Chuang LM, Almaghamsi A, Zilov A, Chen JW, Lavalle-González FJ. Safety and effectiveness of biphasic insulin aspart 30 in people with type 2 diabetes switching from basal–bolus insulin regimens in the A1chieve study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8:111–7.

Akalın S, Araz M, Balcı MK, et al. Biphasic insulin analogues in type 2 diabetes: expert panel recommendations. Turk Jem. 2011;15:51–6.

Randløv J, Poulsen JU. How much do forgotten insulin injections matter to hemoglobin A1c in people with diabetes? A simulation study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:229–35.

Currie CJ, Peyrot M, Morgan CL, et al. The impact of treatment noncompliance on mortality in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1279–84.

Wei W, Pan C, Xie L, Baser O. Real-world insulin treatment persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:52–61.

Rubin RR. Adherence to pharmacologic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 5A):27S–34S.

Nau DP. Recommendations for improving adherence to type 2 diabetes mellitus therapy—focus on optimizing oral and non-insulin therapies. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(3 Suppl):S49–54.

Vijan S, Hayward RA, Ronis DL, Hofer TP. Brief report: the burden of diabetes therapy: implications for the design of effective patient-centered treatment regimens. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:479–82.

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Guzman S, Villa-Caballero L, Edelman SV. Psychological insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the scope of the problem. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2543–5.

Haque M, Emerson SH, Dennison CR, Navsa M, Levitt NS. Barriers to initiating insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in public-sector primary health care centres in Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 2005;95:798–802.

Barnett A, Begg A, Dyson P, Feher M, Hamilton S, Munro N. Insulin for type 2 diabetes: choosing a second-line insulin regimen. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1647–53.

Unnikrishnan AG, Tibaldi J, Hadley-Brown M, et al. Practical guidance on intensification of insulin therapy with BIAsp 30: a consensus statement. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1571–7.

Giugliano D, Tracz M, Shah S, et al. Initiation and gradual intensification of premixed insulin lispro therapy versus basal ± mealtime insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes eating light breakfasts. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:372–80.

Brito M, Ligthelm RJ, Boemi M, et al. Intensifying existing premix therapy (BIAsp 30) with BIAsp 50 and BIAsp 70: a consensus statement. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:152–60.

Acknowledgments

The meeting was supported by Novo Nordisk Region IO A/S. The article processing charges for this publication were funded by Novo Nordisk Region IO A/S. The recommendations, and the evidence base used to formulate them, are not restricted to any one company’s products, and the authors take full responsibility for the contents of the article. The article was reviewed by Novo Nordisk for medical accuracy. The authors warmly thank Alana Philips, Novo Nordisk Australia, for the initial concept and for her support in the development of the guidelines. The authors are also very grateful to Dr. Séan Barklie, Tauranga, New Zealand, and Clinical Associate Professor Mark Kennedy, Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne, Australia, for reading and providing critical review comments on a draft of the manuscript. Writing and editorial support were provided by Watermeadow Medical (supported by Novo Nordisk). All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

T. Wu has received support from Novo Nordisk, MSD, Eli Lilly, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, and GlaxoSmithKline. He has been a consultant for Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Eli Lilly, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, and Roche, and a paid instructor with Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Eli Lilly, and MSD. B. Betty has been a paid instructor with Novo Nordisk. M. Downie has received honoraria as a speaker for Novo Nordisk, Novartis, and Sanofi. G. Kilov has been a member of an advisory board for Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Novartis, Lilly, and Takeda, and received payment for the provision of peer-to-peer education for Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Novartis, Lilly, Takeda, and MSD. G. Fulcher has received research support from Novo Nordisk, and been a paid consultant for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, and Novartis. M. Khanolkar, B. Orr-Walker, and G. Senator have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author contributions

Chair of expert panel meeting and final arbiter on the content of the guidelines: T. Wu. Participation in expert panel meeting and discussion of content: all authors. Critical revision of article: all authors. Approval of article: all authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, T., Betty, B., Downie, M. et al. Practical Guidance on the Use of Premix Insulin Analogs in Initiating, Intensifying, or Switching Insulin Regimens in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther 6, 273–287 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-015-0116-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-015-0116-0