Abstract

Background

Opportunistic screening using hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) may improve detection of undiagnosed diabetes but remains controversial.

Objective

To evaluate the predictive validity of HbA1c as a screening test for undiagnosed diabetes in a risk-stratified sample of the US population.

Design

Weighted cross-sectional analysis of diabetes risk factors, HbA1c, and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2004.

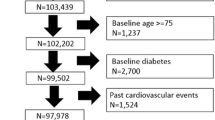

Subjects

Six thousand seven hundred and twenty-three NHANES participants from morning examination session, aged ≥18 years and without prior physician-diagnosed diabetes.

Measurements

HbA1c and undiagnosed diabetes defined by FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l (126 mg/dl).

Results

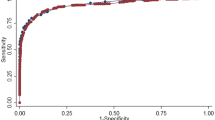

The estimated prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in the US population was 2.8% (5.5 million people). HbA1c had strong correlation with undiagnosed diabetes, with an area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of 0.93. Independent predictors of undiagnosed diabetes were older age, male sex, black race, hypertension, elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. We derived a risk score for undiagnosed diabetes and stratified participants into low (0.44% prevalence), moderate (4.1% prevalence), and high (11.1% prevalence) risk subgroups. In moderate and high risk groups, a threshold HbA1c value ≥ 6.1% identified patients requiring confirmatory FPG; HbA1c ≤ 5.4% identified patients for whom diabetes could be reliably excluded. Intermediate HbA1c (5.5–6.0%) may exclude diabetes in moderate, but not high risk groups).

Conclusions

Risk stratification improves the predictive validity of HbA1c in screening for undiagnosed diabetes in the US population. Although opportunistic screening with HbA1c would improve detection of undiagnosed diabetes, cost-effectiveness studies are needed before implementation of specific screening strategies using HbA1c.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2005. Rev ed. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005.

Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the US population. Diabetes Care. 2006; 29:1263–8.

Harris MI, Klein R, Welborn TA, Knullman MW. Onset of NIDDM occurs at least 4–7 years before clinical diagnosis. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:815–9.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. 2nd ed. With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. Section 5: Diabetes. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, November 2000.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: Recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003;1:212–4.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2007. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:S4–S41.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837–53.

Woerle HF, Pimenta WP, Meyer C, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications of relationships between fasting, 2-hour postchallenge plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1c values. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1627–32.

Peters AL, Davidson MB, Schriger DL, Hasselblad V. A clinical approach for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: An analysis using glycosylated hemoglobin levels. JAMA. 1996;276:1246–52.

Rohlfing CL, Little RR, Wiedmeyer HM, et al. Use of GHb (HbA1c) in screening for undiagnosed diabetes in the US population. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:187–91.

Davidson MB, Schriger DL, Peters AL, Lorber B. Relationship between fasting plasma glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin: Potential for false-positive diagnoses of type 2 diabetes using new diagnostic criteria. JAMA. 1999;281:1203–10.

Perry RC, Shankar RR, Fineberg N, McGill J, Baron AD, Early Diabetes Intervention Program (EDIP). HbA1c Measurement improves the detection of type 2 diabetes in high-risk individuals with nondiagnostic levels of fasting plasma glucose: The Early Diabetes Intervention Program (EDIP). Diabetes Care. 2001;24:465–71.

Edelman D, Edwards LJ, Olsen MK, Dudley TK, Harris AC, Blackwell DK, Oddone EZ. Screening for diabetes in an outpatient clinic population. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:23–8.

Greci LS, Kailasam M, Malkani S, Katz DL, Hulinsky I, Ahmadi R, Nawaz H. Utility of HbA1c levels for diabetes case finding in hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1064–8.

Miyazaki M, Kubo M, Kiyohara Y, et al. Comparison of diagnostic methods for diabetes mellitus based on prevalence of retinopathy in a Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1411–5.

Edelman D, Olsen MK, Dudley TK, Harris AC, Oddone EZ. Utility of Hemoglobin A1c in Predicting Diabetes Risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1175–80.

Ellison RL, Elliott R, Moyes SA. HbA1c screening for undiagnosed diabetes in New Zealand. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005;21:65–70.

Peter R, Luzio SD, Dunseath G, Pauvaday V, Mustafa N, Owens DR. Relationship between HbA1c and indices of glucose tolerance derived from a standardized meal test in newly diagnosed treatment naïve subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23:990–5.

Nakagami T, Tominaga M, Nishimura R, Yoskiike N, Daimon M, Oizumi T, Tajima N. Is the measurement of glycated hemoglobin A1c alone an efficient screening test for undiagnosed diabetes? Japan national diabetes survey [online]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;76:251–6.

Buell C, Kermah D, Davidson MB. Utility of hemoglobin A1c for diabetes screening in the 1999–2004 NHANES population. Diabetes Care, 2007; [In press].

Vinicor F. When is diabetes diabetes [editorial]. JAMA. 1999;281:1222–4.

Davidson MB, Schriger DL, Peters AL, Lorber B. Glycosylated hemoglobin as a diagnostic test for type 2 diabetes mellitus [editorial]. JAMA. 2000;283:605–6.

Papoz L, Favier F, Clabé A. GHb (HbA1c) is more sensitive than fasting blood glucose as a screening test for diabetes [editorial]. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1206–7.

Herman WH, Engelgau MM, Zhang Y, Brown MB. Use of GHb (HbA1c) to screen for undiagnosed diabetes in the US population [editorial]. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1207.

Davidson MB. Catch-22 [editorial]. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:414.

Little RR. Glycated hemoglobin standardization—National glycohemoglobin standardization program (NGSP) perspective. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:1191–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999–2004. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/datalink.htm. Accessed April 25, 2008.

Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97.

Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: Increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-Dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:416–20.

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:40–4.

Bamber D. The area above the ordinal dominance graph and the area below the receiver operating characteristic graph. J Math Psychol. 1975;12:387–415.

Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance in US adults: The third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:518–24.

Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the US population: National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1263–8.

Hing E, Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National ambulatory medical care survey: 2004 summary. Adv Data. 2006;374:1–33.

Ealovega MW, Tabaei BP, Brandle M, Burke R, Herman WH. Opportunistic screening for diabetes in routine medical practice. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:9–12.

Tabaei BP, Burke R, Constance A, et al. Community-based screening for diabetes in Michigan. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:668–70.

Rolka DB, Narayan KM, Thompson TJ, et al. Performance of recommended screening tests for undiagnosed diabetes and dysglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1899–903.

CDC Cost-effectiveness study group. The cost-effectiveness of screening for type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 1998;280:1757–63.

Stern MP, Williams K, Haffner SM. Identification of persons at high-risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: do we need the oral glucose tolerance test? Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:575–81.

Motta M, Bennati E, Ferlito L, Passamonte M, Malaguarnera M. Value and significance of new diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus in older people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45:103–8.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Ginde was supported by the Emergency Medicine Foundation Research Fellowship grant (Dallas, TX).

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Ginde has received investigator-initiated research funding from Bayer and Novo Nordisk in the past 3 years. Dr. Camargo has received financial support from a variety of groups for participation in conferences, consulting, and medical research. Over the past 3 years, industry sponsors with an interest in diabetes were AstraZeneca, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Cagliero and Dr. Nathan have no financial disclosures to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ginde, A.A., Cagliero, E., Nathan, D.M. et al. Value of Risk Stratification to Increase the Predictive Validity of HbA1c in Screening for Undiagnosed Diabetes in the US Population. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 1346–1353 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0661-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0661-6