Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

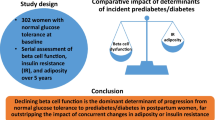

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) identifies a population of young women at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes and thus provides an excellent model for studying early events in the natural history of this disease. Adiponectin, a novel adipocyte-derived protein with insulin-sensitising properties, has been proposed as a factor linking insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. We conducted the current investigation to determine whether adiponectin is associated with beta cell dysfunction in GDM.

Methods

We studied 180 women undergoing OGTT in late pregnancy. Based on the OGTT results, participants were stratified into three groups: (1) NGT (n=93); (2) IGT (n=39); and (3) GDM (n=48). First-phase insulin secretion was determined using a validated index previously proposed by Stumvoll. Insulin sensitivity was assessed using the validated OGTT insulin sensitivity index of Matsuda and DeFronzo (ISOGTT).

Results

To evaluate beta cell function in relation to ambient insulin sensitivity, an insulin secretion-sensitivity index (ISSI) was derived from the product of the Stumvoll index and the ISOGTT, based on the existence of the predicted hyperbolic relationship between these two measures. Mean ISSI was highest in the NGT group (6,731), followed by that in the IGT group (4,976) and then that in the GDM group (3,300) (overall p<0.0001), compatible with the notion of declining beta cell function across these glucose tolerance groups. Importantly, adiponectin was significantly correlated with ISSI (r=0.34, p<0.0001), with a stepwise increase in mean ISSI observed per tertile of adiponectin concentration (trend p<0.0001). In multivariate linear regression analysis, ISSI was positively correlated with adiponectin and negatively correlated with GDM, IGT and C-reactive protein (r 2=0.54).

Conclusions/interpretation

Adiponectin concentration is an independent correlate of beta cell function in late pregnancy. As such, adiponectin may play a key role in mediating insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction in the pathogenesis of diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pathophysiological hallmarks of type 2 diabetes mellitus are insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction [1]. In healthy individuals, pancreatic insulin secretion is linked to peripheral insulin sensitivity through a postulated negative feedback loop that allows the beta cells to compensate for any change in whole-body insulin sensitivity by a proportionate and reciprocal change in insulin secretion. Accordingly, a hyperbolic relationship exists between insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity, such that the product of these two parameters, which has been referred to as the disposition index, is constant for a given degree of glucose tolerance [2, 3]. In the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, progressive deterioration of beta cell function leads to an inability to secrete sufficient insulin to compensate for insulin resistance, a process reflected by a concomitant decline in the disposition index [4, 5]. Given the requirement of both beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance, a ‘two-hit’ model of the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes has been suggested [6]. Alternatively, a so-called ‘closed-loop’ model has also been proposed, which postulates that diabetes may result from a failure of appropriate signalling between insulin-responsive peripheral tissues and insulin-secreting beta cells [4, 6]. In this context, understanding the molecular signals linking insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion would be of great interest.

Adipocyte-derived mediators such as NEFAs and TNF-α have been proposed as factors that may link insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes [7]. Another candidate is adiponectin, a novel adipocytokine with pleiotropic effects, including putative insulin-sensitising, anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory properties [8, 9]. Consistent with the low circulating levels of adiponectin observed in type 2 diabetes, adiponectin concentration is inversely related to both insulin resistance and central adiposity [10–13]. Moreover, low baseline adiponectin concentration can predict the future development of insulin resistance, while elevated baseline levels have been shown to be protective against the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes [14–18]. Importantly, however, while adiponectin has emerged as an apparent mediator of insulin resistance, its potential association with beta cell dysfunction has received limited attention.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) identifies a population of women at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes and thus potentially provides a model of early events in the natural history of type 2 diabetes [19]. GDM arises in a subset of young women in whom the considerable acquired insulin resistance of late pregnancy unmasks a previously unrecognised beta cell defect [20]. Accordingly, this population of women has been reported to exhibit a reduced mean disposition index both during and after pregnancy, when compared with normoglycaemic counterparts [20, 21]. In a cross-sectional study of 180 women in the third trimester, we recently demonstrated that women with GDM also exhibit hypoadiponectinaemia when compared with normoglycaemic controls, after adjustment for covariates including insulin resistance [22]. Given this finding, we hypothesised that beta cell dysfunction may be related to reduced adiponectin concentration. Thus, the current analysis was undertaken to evaluate the relationship between adiponectin concentration and beta cell function in this cohort of women across different strata of glucose tolerance in late pregnancy.

Subjects and methods

The study design, protocol and laboratory methods have been fully described elsewhere [23]. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Mount Sinai Hospital and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Subjects

Study participants were 180 pregnant women attending outpatient obstetrics clinics, who had been referred for a 100-g OGTT following an abnormal result on a screening 50-g glucose challenge test (plasma glucose ≥7.8 mmol/l 1 h post-challenge). Exclusion criteria were: (1) pre-existing chronic medical conditions that may affect acute-phase markers, including established diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, collagen vascular diseases, inflammatory bowel disease and chronic inflammatory conditions; or (2) current use of corticosteroids. Participants were recruited prior to undergoing the 100-g OGTT.

Baseline evaluation

On the day of the OGTT, demographic and historical information was collected by interviewer-administered questionnaire. Data collected were: (1) patient demographics; (2) information regarding current pregnancy including illnesses, infections and medications; (3) personal medical, obstetrical and smoking history; and (4) family history. Specific GDM risk factors were assessed including age, ethnicity, pre-pregnancy weight, weight gain during pregnancy, personal history of GDM, previous delivery of a macrosomic infant and a family history of GDM, macrosomic infant or type 2 diabetes. Anthropometric measurements of height (measured to nearest 0.5 cm) and weight (measured to nearest 0.1 kg) were obtained using a medical scale.

Laboratory measurements

The 100-g OGTT was performed in the morning after an overnight fast. Venous blood samples were drawn at baseline and 60, 120 and 180 min after ingestion of a standard 100-g glucose load. Plasma adiponectin concentration was measured at 180 min (adiponectin level is not affected by food intake [13]) by radioimmunoassay (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO, USA) with a CV of 9.3% [12]. Fasting C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration was determined using the Behring BN100 and the N high-sensitivity C-reactive protein reagent (Dade-Behring, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Specific insulin was measured at each of the four time points of the OGTT using the Roche Elecsys 1010 immunoassay analyser and the electrochemiluminescence immunoassay kit. This assay shows 0.05% cross-reactivity to intact human proinsulin and the primary circulating split form des-31, 32 proinsulin.

Glycaemic status

The OGTT stratified participants into three glycaemic tolerance groups: (1) GDM, as defined by the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) criteria (requires at least two of the following: [i] fasting glucose >5.8 mmol/l, [ii] 1-h post-challenge glucose >10.6 mmol/l, [iii] 2-h post-challenge glucose >9.2 mmol/l, or [iv] 3-h post-challenge glucose >8.1 mmol/l); (2) IGT, as defined by NDDG criteria (requires one of the above GDM criteria); and (3) NGT, defined as subjects not meeting any of the GDM or IGT criteria [24].

Insulin secretion and sensitivity indices

Several models have been previously proposed for evaluation of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion using measurements from the OGTT. In this study, we used the following models of insulin sensitivity: (1) the OGTT insulin sensitivity index of Matsuda and DeFronzo (ISOGTT; (2) the QUICKI (quantitative insulin sensitivity check index) model; and (3) the homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). The ISOGTT model of Matsuda and DeFronzo for insulin sensitivity is defined by the following formula: 10,000/square root(Gluc0×Ins0×mean Gluc×mean Ins), where Ins y and Gluc y represent plasma insulin and glucose values, respectively, at time y minutes during the OGTT [25]. Mean glucose and mean insulin were calculated using measurements at baseline and after 60, 120 and 180 min during the OGTT. The QUICKI model of insulin sensitivity is defined by the following formula: 1/(log[Ins0]+log[Gluc0]) [26]. HOMA-IR is defined as follows: (Gluc0×Ins0)/22.5 [27]. The ISOGTT, QUICKI and HOMA-IR indices have all been validated in pregnancy and in GDM [28]. In this validation study in pregnant patients, the ISOGTT index showed better correlation with insulin sensitivity derived using the euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp technique than either the QUICKI or the HOMA-IR model.

We used the following three measures of insulin secretion: (1) the Stumvoll first-phase measure of insulin secretion; (2) the Stumvoll second-phase measure of insulin secretion; and (3) the homeostasis model of assessment for beta cell (HOMA-B). The Stumvoll first-phase measure of insulin secretion is defined by the following formula: 1,194+4.724×Ins0−117.0×Gluc60+1.414×Ins60 [29]. The Stumvoll second-phase measure of insulin secretion is defined as follows: 295+0.349×Ins60−25.72×Gluc60+1.107×Ins0 [29]. The Stumvoll first- and second-phase insulin secretion formulae were derived using multiple linear regression models to predict directly measured first- and second-phase insulin release during hyperglycaemic clamp studies [29, 30]. HOMA-B is defined by the following formula: (20×Ins0)/(Gluc0−3.5) [27]. The HOMA-B formula was derived from a computer model of the interaction between fasting insulin and glucose [27]. Neither HOMA-B nor the Stumvoll indices have been validated in pregnancy. However, these measures have been validated in a number of other populations and have been shown to predict diabetes in prospective studies [30–33]. The incremental area under the insulin curve (AUCins) and the incremental area under the glucose curve (AUCglu) were calculated using the trapezoidal rule.

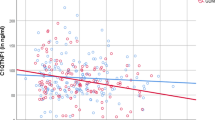

Using Origin Version 6 (Microcal, Northampton, MA, USA), the relationship between the Stumvoll first-phase index and the ISOGTT index of insulin sensitivity was approximated by the following rectangular hyperbolic function: Stumvoll first-phase index=constant/ISOGTT. This relationship can be alternatively stated as Stumvoll first-phase index×ISOGTT=constant. To evaluate beta cell function in the context of ambient insulin resistance, an insulin secretion-sensitivity index (ISSI) was derived from the product of the Stumvoll first-phase index and ISOGTT.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Means and SDs or proportions were presented according to glucose tolerance group, and ANOVA and chi square tests were used to assess univariate differences between continuous and categorical variables respectively. The distributions of CRP, adiponectin, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, ISOGTT and all surrogate measures of insulin secretion were substantially skewed, and thus medians and interquartile ranges were presented for these variables (Table 1). In addition, the natural logarithmic transformations of CRP, adiponectin, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, ISOGTT and all surrogate measures of insulin secretion were used in univariate and multivariate analyses, with back-transformed results from multivariate analyses presented in tables and figures. Parity and smoking exposure were defined as indicated previously [22]. Univariate associations of adiponectin and CRP with ISSI were assessed by Spearman correlation analysis. Finally, multiple linear regression analysis was used to determine which factors were significantly and independently associated with variation in log ISSI. A forward selection approach was used, and the following independent variables were considered: age, ethnicity, pre-pregnancy BMI, previous GDM, family history of type 2 diabetes, adiponectin, CRP, IGT and GDM. The best-fit curves for ISSI in the entire dataset (Fig. 1), by glucose tolerance status (Fig. 2) and by adiponectin tertile (Fig. 3) were determined using Origin Version 6 (Microcal, Northampton, MA, USA).

Insulin secretion–sensitivity index (ISSI) curves according to adiponectin tertile. a Tertile 1 (4.1–12.3 μg/ml); b tertile 2 (12.4–17.0 μg/ml); c tertile 3 (17.2–39.4 μg/ml); and d composite graph showing all three curves (tertile 1, solid line; tertile 2, dashed line; tertile 3, dotted line) (trend p<0.0001)

Results

As described in an earlier report, there were no significant differences between the glycaemic tolerance groups in terms of age, weeks of gestation, pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain during pregnancy, parity, smoking exposure, ethnicity or family history of type 2 diabetes or GDM (Table 1 and [22]). In the GDM group, 18.8% of subjects had a previous history of GDM or delivery of a macrosomic infant, compared with 10.3% of IGT subjects and 4.3% of NGT subjects (overall p=0.0206). CRP concentration was not significantly different across the three glycaemic tolerance strata, while median adiponectin concentration was highest in the NGT group (16.2 μg/ml), followed by that in the IGT group (15.3 μg/ml) and then that in the GDM group (12.3 μg/ml) (overall p=0.0004).

Metabolic characteristics pertaining to insulin sensitivity and secretion for the three glycaemic tolerance groups are presented in Table 1. Both measures of insulin sensitivity, ISOGTT and QUICKI, showed the greatest insulin sensitivity in the NGT group, followed by that in the IGT group and then that in the GDM group (overall p<0.0001 and p=0.0006, respectively). Consistent with these observations, both measures of insulin resistance, HOMA-IR and fasting insulin, demonstrated that the GDM subjects had the highest insulin resistance, followed by the IGT patients and then the NGT subjects (overall p=0.0002 and p=0.0036, respectively).

Among measures of insulin secretion, the mean unadjusted Stumvoll first-phase index was highest in the NGT group (1,413.3), followed by that in the IGT group (1,255.1) and then that in the GDM group (1,218.2) (overall p=0.0154). The Stumvoll second-phase measure showed a similar pattern, though at borderline significance (overall p=0.0590). HOMA-B was not significantly different between the three groups.

Plotting the Stumvoll first-phase index vs ISOGTT revealed the expected hyperbolic relationship between a measure of insulin secretion (Stumvoll first-phase) and a measure of insulin sensitivity (ISOGTT) (Fig. 1). Thus, to evaluate beta cell function in the context of ambient insulin sensitivity, ISSI was derived from the product of the Stumvoll first-phase index and the ISOGTT. When stratified according to glucose tolerance status, the ISSI hyperbolae showed a progressive shift towards the origin from NGT to IGT to GDM, indicative of poorer beta cell function with worsening glucose tolerance (Fig. 2). This pattern was further reflected in the trend of decreasing mean ISSI score from NGT (6731) to IGT (4976) to GDM (3300) (overall p<0.0001).

In univariate Spearman correlation analysis, ISSI was significantly correlated with adiponectin concentration (r=0.34, p<0.0001) and inversely related to CRP concentration (r=−0.17, p=0.022). When stratified according to tertile of adiponectin concentration, the ISSI hyperbolae displayed a progressive shift towards the origin associated with decreasing adiponectin tertile (trend p<0.0001), consistent with an association between declining beta cell function and reduced adiponectin concentration (Fig. 3).

To identify independent determinants of beta cell function, forward stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was performed with logarithmically transformed ISSI as the dependent variable. ISSI was negatively correlated with GDM, IGT and CRP, while adiponectin emerged as the sole positive independent correlate of this index (Table 2). This model reconciled 54.01% of the variation in ISSI. Furthermore, adjustment for potential covariates, including age, ethnicity, pre-pregnancy BMI, previous GDM and family history of type 2 diabetes, did not significantly change the model, with GDM, IGT, CRP and adiponectin again emerging as independent predictors (data not shown).

The ratio of a measure of insulin secretion, the insulinogenic index, to a measure of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) has previously been used to evaluate beta cell function [1, 32, 34]. The insulinogenic index (defined as the ratio of incremental change in insulin:incremental change in glucose over the first 30 min of an OGTT) is highly correlated to the ratio of the incremental area under the insulin curve (AUCins):incremental area under the glucose curve (AUCglu) over the entire time course of the OGTT (S. E. Kahn, unpublished observation). Thus, the ratio of AUCins/AUCglu:HOMA-IR provides an alternate measure of beta cell function. As a measure of robustness of the findings reported here, multiple linear regression analysis was performed, using the logarithmic transformation of the ratio of AUCins/AUCglu:HOMA-IR as the dependent variable. Consistent with the results of the ISSI multivariate analysis, adiponectin again emerged as an independent predictor variable (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that adiponectin concentration is an independent correlate of beta cell function in late pregnancy. Reduced adiponectin concentration is associated with beta cell dysfunction, as modelled by the insulin secretion-sensitivity index, a measure of beta cell responsiveness in the context of ambient insulin resistance. To date, hypoadiponectinaemia in both GDM and type 2 diabetes has been mainly characterised as a mediator of insulin resistance. The current study, however, raises the important possibility that adiponectin may be a factor linking insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction in the pathogenesis of diabetes.

The physiological feedback loop linking whole-body insulin sensitivity and beta cell responsiveness dictates that unbiased evaluation of beta cell function must take into account the impact of prevailing insulin sensitivity. Accordingly, the disposition index has been promoted as an important integrated measure of beta cell function in vivo. The disposition index is defined as the product of the acute insulin response to glucose (AIRg) and the insulin sensitivity index (S I), measures derived from the IVGTT [2, 3]. Given the requirement of the labour-intensive IVGTT, however, the disposition index has not been widely applicable to the clinical setting and has generally been reserved for small- to mid-sized research studies.

In the current study, ISSI was derived by applying the concept of the disposition index to measurements obtained during a standard OGTT. ISSI is defined as the product of the Stumvoll first-phase index of insulin secretion and the ISOGTT index of insulin sensitivity. The Stumvoll first-phase model has been previously validated using the hyperglycaemic clamp technique [29]. Similarly, in validation studies in pregnant patients, the ISOGTT index showed better correlation with insulin sensitivity derived using the euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp technique than either the QUICKI or the HOMA-IR model [28]. Using these two validated indices, ISSI provides a simple and convenient approach for modelling beta cell function using the OGTT. Conceptually, the use of ISSI in this way is similar to the recent approach of evaluating beta cell function using the ratio of the insulinogenic index (a measure of insulin secretion):HOMA-IR [1, 32, 34]. Specifically, given the inverse relationship between insulin sensitivity and resistance, the product of a measure of insulin secretion and an index of insulin sensitivity (i.e. ISSI) would be expected to simulate the ratio of insulin secretion:insulin resistance. Furthermore, the use of ISSI to evaluate beta cell function is supported by the observed hyperbolic relationship between the Stumvoll first-phase index of insulin secretion and the ISOGTT measure of insulin sensitivity. Finally, the biological validity of this approach is supported by the fact that, as shown in Fig. 2, ISSI can unmask the underlying differences in beta cell function associated with NGT, IGT and GDM, respectively, that were originally demonstrated using the disposition index. As such, we propose ISSI as a novel and convenient measure of beta cell function using the standard OGTT that may be useful both in a clinical setting and in large research studies. Further study in this regard is warranted.

In the current study, we have demonstrated an independent association between adiponectin concentration and ISSI. This finding is consistent with a previous report in which adiponectin and disposition index were studied concurrently. In a small longitudinal study of 13 obese women undergoing bariatric surgery, Guldstrand and colleagues demonstrated that adiponectin concentration is an independent determinant of the improvement in disposition index associated with significant weight reduction [35]. Although a recent study in post-partum women failed to detect an independent association between adiponectin and disposition index, the ability to address this question in that paper may have been undermined by the inclusion of both S I and disposition index as covariates in the multivariate analysis of adiponectin [36]. In a recent study of 49 adolescents, Bacha et al. demonstrated that adiponectin is an independent predictor of the proinsulin:insulin ratio, a marker of beta cell dysfunction [37]. The present study thus extends this intriguing association between adiponectin and beta cell function to a much larger patient population across different strata of glucose tolerance during pregnancy.

Previous studies have clearly established an association between hypoadiponectinaemia and insulin resistance in both GDM and type 2 diabetes [10, 22]. In this context, the current findings now raise the hypothesis that reduced adiponectin concentration may contribute to both insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. This idea is consistent with the findings of Yamauchi et al. in studies of transgenic mice overexpressing globular adiponectin in a leptin-deficient ob/ob background [38]. Interestingly, globular adiponectin overexpression afforded diabetes-prone ob/ob mice protection from diabetes that was accompanied by enhanced insulin sensitivity and (unexpectedly) increased insulin secretion, suggestive of improved beta cell function. It was thus speculated that adiponectin may have direct protective effects on beta cells. Indeed, the recent demonstration of marked expression of mRNA species encoding the adiponectin receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 in human and rat beta cells lends further support to this idea [39]. Winzell et al. have suggested a dual action of adiponectin on insulin secretion in insulin-resistant mice [40]. In addition, recent preliminary findings suggest that, in vitro, adiponectin can increase insulin secretion through stimulation of insulin secretory granules in beta cells [41]. Taken together, these data support the possibility that adiponectin may have direct effects on beta cell function.

Although the molecular mechanisms by which adiponectin may exert protective or stimulatory effects on beta cell function are not clear, several potential models may be considered. One potential mechanism could involve the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, which has emerged as a potential mediator of beta cell dysfunction, possibly via disrupted insulin signalling or overproduction of the cytotoxic free radical nitric oxide [7, 42]. Since adiponectin appears to attenuate the effects of TNF-α in both adipose tissue and endothelium [8], adiponectin-mediated antagonism of TNF-α in islet cells may be a mechanism for beta cell protection. Secondly, considering the lipotoxicity theory for beta cell dysfunction, adiponectin may protect beta cells from ectopic fat deposition, as it has previously been shown to reduce intracellular lipid deposition in other tissues such as skeletal muscle [43]. Indeed, treatment with the globular domain of adiponectin has recently been shown to partially protect cultured beta cells from the deleterious effects of fatty acids, including insulin secretory dysfunction and apoptosis [44]. Finally, a third, less likely possibility involves insulin resistance at the level of the pancreas, which has been proposed as a potential factor in the development of beta cell dysfunction [45]. Given its insulin-sensitising effects on peripheral tissues such as muscle and liver, adiponectin could conceivably ameliorate insulin resistance in beta cells as well, leading to improved secretory function.

We recognise that the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes comment on causality in the association between adiponectin concentration and beta cell function. Indeed, chronic insulin resistance has been proposed as a potential cause of the beta cell defect in women with GDM [20]. In the context of this hypothesis, then, the association between hypoadiponectinaemia and beta cell dysfunction in our study may be a reflection of chronic insulin resistance. As such, despite supportive evidence suggesting that adiponectin may have direct effects on beta cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that the current observations reflect an indirect relationship mediated by chronic insulin resistance. Clearly, further study is warranted to address the physiological basis underlying the observed association between adiponectin concentration and beta cell function.

A second potential limitation to consider is the possibility that auto-correlation between our measures of insulin secretion (e.g. Stumvoll first-phase index) and insulin sensitivity (e.g. ISOGTT) may confound interpretation of their apparent hyperbolic relationship. However, if auto-correlation were underlying this relationship, one would not expect subjects with the same insulin sensitivity to exhibit different insulin secretion responses. In the current dataset, however, subjects with the same insulin sensitivity do indeed exhibit very different insulin secretion responses (e.g. depending on glucose tolerance status), as evidenced by the separate ISSI curves by glucose tolerance status shown in Fig. 2. This finding supports the contention that the hyperbolic relationship between the Stumvoll first-phase index and the ISOGTT is not a spurious association on the basis of auto-correlation between the component measures and does indeed provide a measure of beta cell function.

In conclusion, we have introduced ISSI as a novel measure of beta cell function that can be derived from the standard OGTT and, using this index, have demonstrated that adiponectin concentration is an independent correlate of beta cell function in late pregnancy. Hypoadiponectinaemia is thus associated with both insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction in GDM. As such, adiponectin emerges as an important factor potentially linking insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes.

Abbreviations

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- GDM:

-

gestational diabetes mellitus

- HOMA-B:

-

homeostasis model of assessment for beta cell

- HOMA-IR:

-

homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance

- ISOGTT :

-

OGTT insulin sensitivity index of Matsuda and Defronzo

- ISSI:

-

insulin secretion-sensitivity index

- NDDG:

-

National Diabetes Data Group

- QUICKI:

-

quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

- S1 :

-

insulin sensitivity index

References

Kahn SE (2003) The relative contributions of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction to the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 46:3–19

Bergman RN, Phillips LS, Cobelli C (1981) Physiologic evaluation of factors controlling glucose tolerance in man: measurement of insulin sensitivity and β-cell glucose sensitivity from the response to intravenous glucose. J Clin Invest 68:1456–1467

Kahn SE, Prigeon RL, McCulloch DK et al (1993) Quantification of the relationship between insulin sensitivity and β-cell function in human subjects: evidence for a hyperbolic function. Diabetes 42:1663–1672

Bergman RN, Finegood DT, Kahn SE (2002) The evolution of β-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Invest 32[Suppl 3]:35–45

Weyer C, Bogardus C, Mott DM, Pratley RE (1999) The natural history of insulin secretory dysfunction and insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 104:787–794

Bergman RN, Ader M, Huecking K, Van Citters G (2002) Accurate assessment of β-cell function: the hyperbolic correction. Diabetes 51[Suppl 1]:S212–S220

Greenberg AS, McDaniel ML (2002) Identifying the links between obesity, insulin resistance and β-cell function: potential role of adipocyte-derived cytokines in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Invest 32[Suppl 3]24–34

Ukkola O, Santaniemi M (2002) Adiponectin: a link between excess adiposity and associated comorbidities? J Mol Med 80:696–702

Berg AH, Combs TP, Scherer PE (2002) ACRP30/adiponectin: an adipokine regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:84–89

Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S et al (2001) Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 DM: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:1930–1935

Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N et al (1999) Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257:79–93

Cnop M, Havel PJ, Utzschneider KM et al (2003) Relationship of adiponectin to body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity and plasma lipoproteins: evidence for independent roles of age and sex. Diabetologia 46:459–469

Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y et al (2000) Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20:1595–1599

Stefan N, Vozarova B, Funahashi T et al (2002) Plasma adiponectin concentration is associated with skeletal muscle insulin receptor tyrosine phosphorylation, and low plasma concentration precedes a decrease in whole-body insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes 50:1884–1888

Lindsay RS, Funahashi T, Hanson RL et al (2002) Adiponectin and development of type 2 diabetes in the Pima Indian population. Lancet 360:57–58

Spranger J, Kroke A, Mohlig M (2003) Adiponectin and protection against type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lancet 361:226–228

Snehalatha C, Mukesh B, Simon M, Vishwanathan V, Haffner SM, Ramachandran A (2003) Plasma adiponectin is an independent predictor of type 2 diabetes in Asian Indians. Diabetes Care 26:3226–3229

Daimon M, Oizumi T, Saitoh T et al (2003) Decreased serum levels of adiponectin are a risk factor for the progression to type 2 diabetes in the Japanese Population: the Funagata study. Diabetes Care 26:2015–2020

Kjos SL, Buchanan TA (1999) Gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 341:1749–1756

Buchanan TA (2001) Pancreatic β-cell defects in gestational diabetes: implications for the pathogenesis and prevention of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:989–993

Ward WK, Johnston CL, Beard JC, Benedetti TJ, Halter JB, Porte D Jr (1985) Insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion in subjects with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 34:861–869

Retnakaran R, Hanley AJG, Raif N, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B (2004) Reduced adiponectin concentration in women with gestational diabetes: a potential factor in progression to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:799–800

Retnakaran R, Hanley AJG, Raif N, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B (2003) C-reactive protein and gestational diabetes: the central role of maternal obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3507–3512

National Diabetes Data Group (1979) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes 28:1039–1057

Matsuda M, DeFronzo R (1999) Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470

Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K et al (2000) Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:2402–2410

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetes 28:412–419

Kirwan JP, Huston-Presley L, Kalhan SC, Catalano PM (2001) Clinically useful estimates of insulin sensitivity during pregnancy: validation studies in women with normal glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 24:1602–1607

Stumvoll M, Van Haeften TV, Fritsche A, Gerich J (2001) Oral glucose tolerance test indexes for insulin sensitivity and secretion based on various availabilities of sampling times. Diabetes Care 24:796–797

Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W et al (2000) Use of the oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 23:295–301

Phillips DIW, Clark PM, Hales CN, Osmond B (1994) Understanding oral glucose tolerance: comparisons of glucose or insulin measurements during the oral glucose tolerance test with specific measurements of insulin resistance and insulin secretion. Diabet Med 11:286–292

Williams K, Hanley AJG, Haffner SM, Stern MP (2003) Predicting diabetes with insulin secretion measures in the San Antonio Heart Study. Diabetes Metab 29:5S20

Hanson RL, Pratley RE, Bogardus C et al (2000) Evaluation of simple indices of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion for use in epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol 151:190–198

Jensen C, Cnop M, Hull RL, Fujimoto WY, Kahn SE and the American Diabetes Association GENNID Study Group (2002) β-cell function is a major contributor to oral glucose tolerance in high-risk relatives of four ethnic groups in the US. Diabetes 51:2170–2178

Guldstrand M, Ahren B, Adamson U (2003) Improved β-cell function after standardized weight reduction in severely obese subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E557–E565

Winzer C, Wagner O, Festa A et al (2004) Plasma adiponectin, insulin sensitivity, and subclinical inflammation in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 27:1721–1727

Bacha F, Saad R, Gungor N, Arslanian SA (2004) Adiponectin in youth: relationship to visceral adiposity, insulin sensitivity, and β-cell function. Diabetes Care 27:547–552

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H et al (2003) Globular adiponectin protected ob/ob mice from diabetes and ApoE-deficient mice from atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem 278:2461–2468

Kharroubi I, Rasschaert J, Eizirik DL, Cnop M (2003) Expression of adiponectin receptors in pancreatic β-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312:1118–1122

Winzell MS, Nogueiras R, Dieguez C, Ahren B (2004) Dual action of adiponectin on insulin secretion in insulin-resistant mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321:154–160

Okamoto M, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Eto K et al (2004) Adiponectin stimulates insulin secretion via stimulation of insulin secretory granule. Diabetes 53[Suppl 2]:A39

Kwon G, Xu G, Marshall CA, McDaniel ML (1999) Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced pancreatic beta-cell insulin resistance is mediated by nitric oxide and prevented by 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 and aminoguanidine: a role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation and inos expression. J Biol Chem 274:18702–18708

Thamer C, Machann J, Tschritter O et al (2002) Relationship between serum adiponectin concentration and intramyocellular lipid stores in humans. Horm Metab Res 34:646–649

Rakatzi I, Mueller H, Ritzeler O, Tennagels N, Eckel J (2004) Adiponectin counteracts cytokine- and fatty acid-induced apoptosis in the pancreatic beta-cell line INS-1. Diabetologia 47:249–258

Cavaghan MK, Ehrmann DA, Polonsky KS (2000) Interactions between insulin resistance and insulin secretion in the development of glucose intolerance. J Clin Invest 106:329–333

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Mount Sinai Hospital Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Nancy Hutton and Mount Sinai Hospital Patient Care Services, and Maureen Lee MLT and the J. A. Little Lipid Research Laboratory. This study was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). R. Retnakaran is supported by a CIHR Fellowship and A. J. Hanley is supported through a Canadian Diabetes Association Scholarship. S. E. Kahn is supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veteran Affairs and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant DK-02654. B. Zinman holds the Sam and Judy Pencer Family Chair in Diabetes Research at Mount Sinai Hospital and University of Toronto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Retnakaran, R., Hanley, A.J.G., Raif, N. et al. Adiponectin and beta cell dysfunction in gestational diabetes: pathophysiological implications. Diabetologia 48, 993–1001 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-1710-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-1710-x