-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jadienne H. Lord, Mackenzie T. Young, Meredith A. Gruhn, Margaret Grey, Alan M. Delamater, Sarah S. Jaser, Effect of Race and Marital Status on Mothers’ Observed Parenting and Adolescent Adjustment in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 40, Issue 1, January/February 2015, Pages 132–143, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsu078

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objective To examine demographic differences in parenting behaviors and adjustment in youth with type 1 diabetes. Methods Adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment was assessed via self-reports and parent reports, and clinical data were obtained from adolescents’ medical records. Mother–adolescent dyads (N = 93) engaged in a videotaped discussion task, which was coded for observed parenting behaviors. Results Single and non-White mothers exhibited significantly more overinvolved and less collaborative parenting behaviors. Higher levels of overinvolved parenting and lower levels of collaborative parenting were associated with poorer adolescent adjustment (i.e., higher levels of externalizing problems). Observed parenting was not significantly associated with glycemic control. There was an indirect effect of marital status and race/ethnicity on externalizing behaviors through parenting. Conclusions The current study highlights parenting as a potential target for interventions, especially in single and minority mothers, to improve adjustment in this population.

Each year >15,000 children and adolescents are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D), making it one of the most common chronic childhood illnesses in the United States. The management of T1D requires lifelong monitoring and treatment, including multiple daily injections/boluses, monitoring carbohydrate intake and activity levels, and frequently checking blood glucose levels (American Diabetes Association, 2014). During the transition into adolescence, a developmental period marked by significant decline in diabetes outcomes, the primary responsibility for diabetes management shifts from parent to child (Wiebe et al., 2014). The most rapid deterioration is found in minorities and adolescents from low-income and single-parent homes, who have higher risks for suboptimal adherence to treatment regimens and glycemic control (Anderson & McKay, 2011; Neylon, O'Connell, Skinner, & Cameron, 2013). However, the mechanisms of risk for these disparities are not yet fully understood. Parental monitoring, family support, and collaboration are key factors in facilitating effective diabetes management (Ellis et al., 2007; Wysocki et al., 2009), and differences in parenting may help to explain disparities in diabetes outcomes and adjustment.

It is well-known that family environment and parenting are important factors that contribute to adolescents’ diabetes management and behavioral adjustment (Berg et al., 2008; Jaser, 2011). While parental involvement that is perceived as collaborative has been associated with better glycemic control, quality of life, and fewer depressive symptoms in youth (Ellis et al., 2007; Wiebe et al., 2005), evidence suggests that overinvolved, harsh, or intrusive parenting behaviors significantly contribute to the development of internalizing and externalizing problems in youth (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000). Overinvolved parenting may promote internalizing problems by increasing levels of psychological distress and feelings of depression and hopelessness in offspring (McKee et al., 2007), or it may socialize youth to use coercive and hostile behaviors in family interactions and outside of the family (i.e., externalizing problems; Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006). Given the implications for quality of life and health outcomes in youth, these behaviors are important to consider in the context of T1D (Horton, Berg, Butner, & Wiebe, 2009). Externalizing behaviors, including hyperactivity, aggression, disruptiveness, defiance, and impulsivity, have been shown to interfere with optimal adherence, resulting in poorer glycemic control (Duke et al., 2008), and lower levels of internalizing behaviors predict better adherence in young adolescents with diabetes (Korbel, Wiebe, Berg, & Palmer, 2007). Observational studies provide a more objective perspective on parenting behaviors than parent or child report (Kerig, 2001); however, few studies have directly observed collaborative and intrusive parenting behaviors to corroborate those conclusions.

Differences in Diabetes Outcomes Related to Race/Ethnicity and Marital Status

Minority youth have consistently been at higher risk for poorer glycemic control when compared with White youth (Chalew et al., 2000; Delamater et al., 1999). In one study, for example, glycemic control was significantly worse in Hispanic versus non-Hispanic White youth—despite uniformity of care—and Hispanic youth were less independent in managing their diabetes care (Gallegos-Macias, Macias, Kaufman, Skipper, & Kalishman, 2003). Similarly, African American youth have significantly poorer glycemic control compared with White youth (Kamps, Hempe, & Chalew, 2010), and racial differences in glycemic control have been found to begin shortly after diagnosis and accelerate through adolescence (Frey, Templin, Ellis, Gutai, & Podolski, 2007). Differences in diabetes outcomes have even been found between insured minority youth and White youth receiving care through the same integrated health center (Jacobsen, Black, Li, Reynolds, & Lawrence, 2014), suggesting that there are factors beyond treatment disparities affecting glycemic control.

Marital status has also been identified as a risk factor for poor diabetes outcomes. For example, results from one study showed that children of married parents had better glycemic control than children from single, separated, or divorced parents, and this effect was partially mediated by blood glucose monitoring, an important part of diabetes management (Urbach et al., 2005). Similarly, findings from another study indicated that adolescents of single parents had significantly worse glycemic control as compared with children from two-parent households, and that missed clinic appointments predicted poorer glycemic control in single-parent homes (Thompson, Auslander, & White, 2001). These findings suggest that parents’ marital status may be a risk factor for deteriorating glycemic control during adolescence. Although there is a growing interest in research concerning disparities in diabetes outcomes due to access to quality health care (Valenzuela, La Greca, Hsin, Taylor, & Delamater, 2011), it is importance to investigate behavioral influences, such as parenting, as a potential target for interventions to improve outcomes in youth with T1D (Wysocki et al., 1999; 2008).

Differences in Parenting Related to Race and Marital Status

Research suggests that parenting behaviors can influence both physical and mental health in youth with chronic illnesses (Lim, Wood, Miller, & Simmens, 2011; O’Hara & Holmbeck, 2013). Recent observational studies in pediatric populations revealed that negative parenting behaviors (e.g., hostility, critical behavior) were associated with suboptimal treatment adherence, poor adjustment, and worse health outcomes in adolescents with diabetes and asthma (Jaser & Grey, 2010; Wood et al., 2008). In contrast, observed positive parenting behaviors (i.e., parental warmth and support) were associated with better adherence ratings and improved quality of life (Botello-Harbaum, Nansel, Haynie, Iannotti, & Simons-Morton, 2008). Single parents have consistently been shown to be at increased risk for engaging in negative or ineffective parenting practices, as compared with those who are married (Simons, Beaman, Conger, & Chao, 1993). Similarly, ethnic minority mothers have been shown to exhibit significantly more negative (e.g., hostile, intrusive, neglecting) and less positive (e.g., child-centered, positive reinforcement) parenting behaviors than White mothers (Parent et al., 2014). Some parenting differences have been identified in specific racial/ethnic groups; for example, in a study of a large diverse population, Hispanic parents were significantly higher on adolescent reports of parental monitoring than White parents, and African American parents were lower than White parents on adolescent reports of warmth (Chao & Kanatsu, 2008). One explanation for this difference may be that non-White mothers and single mothers of children, especially those with chronic illness, experience more stress and poorer psychological and physical well-being, factors associated with negative parenting behaviors (Auslander, Thompson, Dreitzer, White, & Santiago, 1997; Eckshtain, Ellis, Kolmodin, & Naar-King, 2010; Forehand et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2001). Additionally, differences in income between racial and ethnic groups may impact parenting. Lower income is related to higher depressive symptoms and less effective parenting in Hispanic and non-Hispanic mothers (Drew et al., 2011; Hashima & Amato, 1994) as well as lower levels of parental acceptance (Drew et al., 2011).

Present Study

Previous research in pediatric populations has shown differences in adolescent adjustment, health outcomes, and parenting related to race/ethnicity and marital status, but these relations have not been fully explored in the context of T1D, and previous studies often relied on self-reported measures of parenting. Thus, we used direct observational methods to examine differences in parenting related to race/ethnicity and marital status as contributors to adjustment and glycemic control in adolescents with T1D. First, we hypothesized that single or minority mothers would exhibit higher levels of overinvolved parenting and lower levels of collaborative parenting behaviors than married or White mothers. Second, we hypothesized that children of single or minority mothers would have poorer overall adjustment (i.e., greater internalizing and externalizing problems, lower quality of life, and worse glycemic control) than children of married or White mothers. Third, we hypothesized that overinvolved parenting behaviors would be associated with poorer adjustment, while collaborative parenting behaviors would be associated with better adjustment. Finally, we examined the indirect effect of marital status on adolescents’ adjustment through parenting behaviors.

Methods

Participants

Adolescents were eligible if they had been diagnosed with T1D since at least 6 months, had no other major health problems, and were able to speak and read English. The age range for adolescents was 10–16 years, chosen to capture the developmental transition when responsibility for diabetes management begins shifting from parent to child (Anderson et al., 2002), and when glycemic control and adherence to the recommended treatment regimen often suffer a decline (Borus & Laffel, 2010). Mothers were eligible to participate if they were currently living with the adolescent and were able to speak and read English. We recruited mothers for our sample because evidence suggests that the mother is generally the primary caregiver responsible for the child’s diabetes management, and mothers typically report more diabetes-related distress than fathers (Whittemore, Jaser, Chao, Jang, & Grey, 2012). Of the 394 families approached, 99 were ineligible, 118 refused (most common reasons were time and distance), 60 expressed interest but were unable to schedule a visit, and 117 completed data (40%). There were no significant differences between those who participated and those who did not on gender (χ2 = 0.67; p > .10), ethnicity (χ2 = 1.90; p > .10), or marital status (χ2 = 0.28; p > .10), but there was a significant difference in maternal education (more of the mothers who participated had college degrees; χ2 = 10.05; p < .01). The current sample included 93 adolescents with T1D and their mothers with complete and usable observational data (some videos were not able to be coded owing to technical difficulties, such as problems with audio quality). The majority of mothers in our sample were White, non-Hispanic (80%), and married/partnered (75%). Additional demographic characteristics are presented in Table I.

Demographic Characteristics (n = 93)

| Adolescent variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| M (SD) | 12.6 (2.3) |

| Range | 10–16 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 44.6 |

| Male | 55.4 |

| Duration of diabetes M (SD) (years) | 4.8 (3.5) |

| Therapy type (%) | |

| Pump | 84 |

| Injections | 16 |

| HbA1c | |

| M (SD) | 7.6 (1.2) |

| Range | 5.4–12.9 |

| Adolescent variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| M (SD) | 12.6 (2.3) |

| Range | 10–16 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 44.6 |

| Male | 55.4 |

| Duration of diabetes M (SD) (years) | 4.8 (3.5) |

| Therapy type (%) | |

| Pump | 84 |

| Injections | 16 |

| HbA1c | |

| M (SD) | 7.6 (1.2) |

| Range | 5.4–12.9 |

| Maternal variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age range (years) | |

| M (SD) | 44.0 (5.7) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 80.6 |

| Black | 4.3 |

| Hispanic | 9.7 |

| Other | 5.4 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Married/ partnered | 75.3 |

| Single | 24.7 |

| Education (%) | |

| Less than high school | 2.2 |

| High school/ GED | 8.6 |

| Associates/ some college | 19.4 |

| College degree | 41.9 |

| Graduate degree | 28.0 |

| Annual family income (%) | |

| Less than $40,000 | 8.6 |

| $40,000–$80,000 | 25.8 |

| Greater than $80,000 | 65.6 |

| Maternal variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age range (years) | |

| M (SD) | 44.0 (5.7) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 80.6 |

| Black | 4.3 |

| Hispanic | 9.7 |

| Other | 5.4 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Married/ partnered | 75.3 |

| Single | 24.7 |

| Education (%) | |

| Less than high school | 2.2 |

| High school/ GED | 8.6 |

| Associates/ some college | 19.4 |

| College degree | 41.9 |

| Graduate degree | 28.0 |

| Annual family income (%) | |

| Less than $40,000 | 8.6 |

| $40,000–$80,000 | 25.8 |

| Greater than $80,000 | 65.6 |

Demographic Characteristics (n = 93)

| Adolescent variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| M (SD) | 12.6 (2.3) |

| Range | 10–16 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 44.6 |

| Male | 55.4 |

| Duration of diabetes M (SD) (years) | 4.8 (3.5) |

| Therapy type (%) | |

| Pump | 84 |

| Injections | 16 |

| HbA1c | |

| M (SD) | 7.6 (1.2) |

| Range | 5.4–12.9 |

| Adolescent variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| M (SD) | 12.6 (2.3) |

| Range | 10–16 |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 44.6 |

| Male | 55.4 |

| Duration of diabetes M (SD) (years) | 4.8 (3.5) |

| Therapy type (%) | |

| Pump | 84 |

| Injections | 16 |

| HbA1c | |

| M (SD) | 7.6 (1.2) |

| Range | 5.4–12.9 |

| Maternal variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age range (years) | |

| M (SD) | 44.0 (5.7) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 80.6 |

| Black | 4.3 |

| Hispanic | 9.7 |

| Other | 5.4 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Married/ partnered | 75.3 |

| Single | 24.7 |

| Education (%) | |

| Less than high school | 2.2 |

| High school/ GED | 8.6 |

| Associates/ some college | 19.4 |

| College degree | 41.9 |

| Graduate degree | 28.0 |

| Annual family income (%) | |

| Less than $40,000 | 8.6 |

| $40,000–$80,000 | 25.8 |

| Greater than $80,000 | 65.6 |

| Maternal variable . | |

|---|---|

| Age range (years) | |

| M (SD) | 44.0 (5.7) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 80.6 |

| Black | 4.3 |

| Hispanic | 9.7 |

| Other | 5.4 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Married/ partnered | 75.3 |

| Single | 24.7 |

| Education (%) | |

| Less than high school | 2.2 |

| High school/ GED | 8.6 |

| Associates/ some college | 19.4 |

| College degree | 41.9 |

| Graduate degree | 28.0 |

| Annual family income (%) | |

| Less than $40,000 | 8.6 |

| $40,000–$80,000 | 25.8 |

| Greater than $80,000 | 65.6 |

Procedures

We recruited adolescents and their mothers from an outpatient pediatric diabetes clinic of a university medical center in the northeastern United States during their regular quarterly clinic visits. Families that were interested in the study scheduled a separate visit to the laboratory. After the adolescent assented and the mother consented to participate in the study, following procedures approved by the university’s institutional review board, they completed the questionnaires and participated in a 15-min videotaped discussion of diabetes stress. To choose the topic for the video interaction, we used parent and child responses on the Response to Stress Questionnaire (Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000), which lists diabetes-specific stressors. Mothers and adolescents rated the frequency of each stressor (e.g., worrying about “bad” numbers, feeling different from others) on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (almost every day). Ratings were summed across mother and adolescent report to determine a common stressor, and each dyad was given a cue card with questions regarding their highest-rated stressor (e.g., What happened the last time you [felt different from others], what kind of emotions do you have when you [are feeling different from others]? How can we reduce this stress?) to guide their discussion during the videotaped interaction. If two stressors were rated equally high, we used the one rated higher by the adolescent. After the 15-min period, the participants had an opportunity to provide feedback regarding their visit, and we compensated them for their time ($20 each).

Measures

Demographics

Mothers completed a questionnaire including questions on race/ethnicity, marital status, maternal education, annual household income, and relationship to the child (adoptive, biological) with T1D. For analyses, marital status was collapsed into two categories: married/partnered and single/divorced (no mother identified as widowed). Similarly, race/ethnicity was collapsed into two categories: White (non-Hispanic) and non-White (including Hispanic, Black, and other).

Diabetes-Related Stress

Mothers and adolescents reported on diabetes-related stress using the T1D version of the Responses to Stress Questionnaire (Connor-Smith et al., 2000). The first 10 items of the measure list topics that are stressful for adolescents with T1D (Davidson, Penney, Muller, & Grey, 2004), such as feeling different from others or having to deal with diabetes care. Respondents reported on the recent (i.e., past 6 months) occurrence of each of the stressors on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = a few times, 2 = many times, and 3 = almost every day).

Parenting Behaviors

We used the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS), a well-established, widely used global coding system, to code observed parenting behaviors. The validity of the IFIRS system has been established against reports from self and other family members using correlational and confirmatory factor analyses (Melby & Conger, 2001), and it has been used successfully across racial and ethnic groups and in pediatric populations (Alderfer et al., 2008).

Two trained coders (bachelor’s level) viewed each video interaction and scored behaviors on a scale from 1 (the focal displays no signs of this behavior) to 9 (the focal frequently displays this behavior at a low to moderate level of intensity or such behavior occurs less frequently but at a high level of intensity), based on the behavior’s frequency, context, affect, intensity, and proportion. Means of the two coders’ scores were used in analyses. The codes selected to measure collaborative parenting include Communication, the extent to which the mother uses appropriate explanations and gives appropriate feedback (e.g., I know that you’re busy, but I think you could check your blood sugar more); Positive Reinforcement, the extent to which the mother responds to her child's desired behavior with praise or rewards (e.g., I’m really proud of how you’ve dealt with all of this); and Listener Responsiveness, the degree to which the mother attends to and validates the child’s statements (e.g., nodding while the child is speaking). The codes selected to measure overinvolved, or intrusive, parenting include Parental Influence, parental attempts to regulate, control or influence the child’s behavior (e.g., I wish you would learn to how to set up your own appointments); Intrusiveness, over-controlling behaviors that are parent-centered and emphasize task completion rather than promoting the child’s autonomy (e.g., I don’t care if you don’t want to talk about your high blood sugars, we have to); and Lecture/Moralizing, the extent to which the parent tells the child how to think in a way that assumes superior wisdom and provides little opportunity for the child to think independently (e.g., You should know better than to leave home without your meter). We determined inter-rater reliability by performing intra-class correlations on each parenting behavior code: Communication .69, Listener Responsiveness .68, Positive Reinforcement .76, Intrusiveness .34, Lecture/Moralizing .69, and Parental Influence .42. Similar to other studies using the IFIRS system (Lim et al., 2011), we combined IFIRS codes to create a composite code for collaborative parenting (α = .83) and overinvolved parenting (α = .71).

Diabetes-Related Variables

We collected data on treatment type (pump vs. injection) from adolescents’ medical records because use of insulin pumps in adolescents has been associated with improved glycemic control (Sherr & Tamborlane, 2008). We used glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) as an objective measure of adolescents’ glycemic control over the most recent 8–12 weeks. A target HbA1c of <7.5% is recommended for adolescents (aged 13–20 years) and <8% for children (aged 6–12 years) (American Diabetes Association, 2014). We performed the analyses of HbA1c with the Bayer Diagnostics DCA2000® machine (normal range = 4.2–6.3%).

Adolescent Adjustment

Internalizing and Externalizing Problems

We used the 113-item Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the 112-item Youth Self Report (YSR) to measure behavior problems in adolescents (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Mothers reported on their adolescents’ behaviors by responding to CBCL items on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = absent, 1 = occurs sometimes, 2 = occurs often), while adolescents reported on their own behaviors with the YSR. For the current study, we used the Externalizing (a composite of rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior subscales) and Internalizing (a composite of anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic complaints subscales) scales. The CBCL and YSR were normed on a large national sample and provide age- and sex-based T-scores. The YSR and CBCL were positively correlated with each other for both the Internalizing (r = .27, p = .01) and Externalizing (r = .56, p < .001) problem scales. To reduce the number of analyses, control for method variance, and increase the sensitivity for assessing these constructs, we created composite variables of internalizing and externalizing symptoms by converting parent and child reports to standardized scores (z-scores) and summing the z-scores for each variable (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). The current sample had excellent internal consistency for the CBCL (α = .97) and the YSR (α = .97).

Quality of Life

We used the 28-item Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) T1D module to assess diabetes-specific quality of life, for which high reliability and validity have been established (Varni et al., 2003). In line with recent recommendations, we used a total diabetes quality-of-life score (Nansel, Weisberg-Benchell, Wysocki, Laffel, & Anderson, 2008), for which higher scores indicate greater problems with quality of life. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was .88.

Data Analysis Plan

We performed statistical analyses using IBM SPSS (v. 21) statistical packages. To test our first hypothesis, that married/partnered and White mothers would show higher levels of positive parenting and lower levels of negative parenting than single/divorced mothers, we conducted Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to analyze the differences in observed collaborative and overinvolved parenting by marital status and race/ethnicity. In addition, we conducted multiple linear regressions to determine the association of race and marital status with observed parenting behaviors, after adjusting for other demographic variables (i.e., maternal education, income). To test our second hypothesis, that adolescent children of married/partnered mothers and White mothers would have better adjustment than adolescent children of single/divorced mothers and non-White mothers, we conducted Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to determine differences in adolescent adjustment (internalizing problems, externalizing problems, quality of life, and HbA1C) by marital status and race/ethnicity. To test our final hypothesis, that parenting would mediate the effects of marital status on adolescent adjustment, we first calculated bivariate correlations to determine the associations between parenting behaviors and adolescent adjustment variables (CBCL and YSR composite score, quality of life, and HbA1c). Following the recommendations of MacKinnon and colleagues (2002, 2007), we tested the indirect effect of marital status on outcomes through parenting using the RMediation package, which provides confidence intervals (CIs) for mediated effects, or the product of two regression coefficients. Mediation is said to occur if the CI does not include zero (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). Testing mediation, or indirect effects, in this way is thought to be more powerful than more traditional tests of mediation, such as those proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), and provides more accurate results than MacKinnon’s earlier PRODCLIN program (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). Parenting variables that were significantly related to marital status and adolescent adjustment (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, PedsQL, or HbA1c) were considered potential mediators.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

As seen in Table I, the average HbA1c was 7.6% (SD = 1.2), with 67.4% of adolescents (aged 13–16 years) meeting the American Diabetes Association target (HbA1c < 7.5%), and 55.1% of children (aged 10–12 years) meeting the target (HbA1c < 8%) (American Diabetes Association, 2014). The majority of mothers in the sample were White, non-Hispanic (80.6%) and married/partnered (75.3%). Socioeconomic status was generally high; 69.9% of mothers completed college, and the median annual household income was >$80,000. In terms of behavior problems, 19% of adolescents and 24% of mothers reported clinically significant levels (T score ≥ 60) of internalizing problems, and 3% of adolescents and 13% of mothers reported clinically significant levels of externalizing problems.

Preliminary Analyses

Data were investigated for multivariate outliers and none was found.1 Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether there was a relationship between the target variables (i.e., parenting behaviors, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, quality of life, and HbA1c) and other demographic variables noted as potential covariates in the literature, including family income, maternal education, and child’s age and sex. Household income was significantly related to two of the six variables: Adolescents from families in the lowest annual income category (<$40K/year) had significantly higher levels of internalizing symptoms and significantly higher HbA1c than those from families in the highest income category (>$80K/year). Maternal education was only related to collaborative parenting, such that mothers with a college degree exhibited higher levels of collaborative parenting than those with less education (F = 11.26, p = .001). There were no significant differences in any of the key variables for child sex. Child age was only related to quality of life, such that older children had more problems with quality of life (r = .28, p = .007).

In addition, we examined the relationship between marital status and other demographic factors, and found that, in our sample, several factors were confounded. First, the relationship between income and marital status was significant, χ2(1, N = 92) = 27.42, p < .001; more married/partnered mothers were from the highest income category (>$80K/year) (90%) than were single mothers (10%). There was not a significant relationship between maternal education and marital status, but the relationship between race/ethnicity and marital status was significant [χ2(1, N = 91) = 18.73, p < .001], such that non-White mothers were more likely to be single (64.7%) than White mothers (35.3%).

Differences in Observed Parenting Related to Race/Ethnicity and Marital Status

In line with our hypothesis, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed significant differences in observed parenting related to race/ethnicity, such that non-White mothers exhibited higher levels of overinvolved parenting and lower levels of collaborative parenting than White mothers (Table II). Significant differences in observed parenting were also found related to marital status, such that single mothers exhibited lower levels of collaborative parenting and higher levels of overinvolved parenting than married mothers.

Demographic Differences in Observed Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Adjustment

| . | Mean rank . | U . | z . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White . | Non-White . | . | . | |

| Collaborative parenting | 50.38 | 34.68 | 483.50 | −2.31* |

| Overinvolved parenting | 44.02 | 57.88 | 3213.50 | −2.04* |

| Quality of life | 42.21 | 53.53 | 3300.50 | −1.22 |

| HbA1c | 43.55 | 59.60 | 478.00 | −2.36* |

| Internalizing problems | 44.32 | 51.95 | 591.00 | −1.14 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.44 | 58.63 | 457.00 | −2.42* |

| . | Mean rank . | U . | z . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White . | Non-White . | . | . | |

| Collaborative parenting | 50.38 | 34.68 | 483.50 | −2.31* |

| Overinvolved parenting | 44.02 | 57.88 | 3213.50 | −2.04* |

| Quality of life | 42.21 | 53.53 | 3300.50 | −1.22 |

| HbA1c | 43.55 | 59.60 | 478.00 | −2.36* |

| Internalizing problems | 44.32 | 51.95 | 591.00 | −1.14 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.44 | 58.63 | 457.00 | −2.42* |

| . | Married . | Single . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative parenting | 54.38 | 24.54 | 288.50 | −4.61*** |

| Overinvolved parenting | 42.87 | 59.57 | 516.00 | −2.58* |

| Quality of life | 43.84 | 56.63 | 583.50 | −1.97* |

| HbA1c | 44.16 | 55.65 | 606.00 | −1.77 |

| Internalizing problems | 43.64 | 52.98 | 621.50 | −1.47 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.79 | 55.50 | 563.50 | −2.00* |

| . | Married . | Single . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative parenting | 54.38 | 24.54 | 288.50 | −4.61*** |

| Overinvolved parenting | 42.87 | 59.57 | 516.00 | −2.58* |

| Quality of life | 43.84 | 56.63 | 583.50 | −1.97* |

| HbA1c | 44.16 | 55.65 | 606.00 | −1.77 |

| Internalizing problems | 43.64 | 52.98 | 621.50 | −1.47 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.79 | 55.50 | 563.50 | −2.00* |

Note. *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Demographic Differences in Observed Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Adjustment

| . | Mean rank . | U . | z . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White . | Non-White . | . | . | |

| Collaborative parenting | 50.38 | 34.68 | 483.50 | −2.31* |

| Overinvolved parenting | 44.02 | 57.88 | 3213.50 | −2.04* |

| Quality of life | 42.21 | 53.53 | 3300.50 | −1.22 |

| HbA1c | 43.55 | 59.60 | 478.00 | −2.36* |

| Internalizing problems | 44.32 | 51.95 | 591.00 | −1.14 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.44 | 58.63 | 457.00 | −2.42* |

| . | Mean rank . | U . | z . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White . | Non-White . | . | . | |

| Collaborative parenting | 50.38 | 34.68 | 483.50 | −2.31* |

| Overinvolved parenting | 44.02 | 57.88 | 3213.50 | −2.04* |

| Quality of life | 42.21 | 53.53 | 3300.50 | −1.22 |

| HbA1c | 43.55 | 59.60 | 478.00 | −2.36* |

| Internalizing problems | 44.32 | 51.95 | 591.00 | −1.14 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.44 | 58.63 | 457.00 | −2.42* |

| . | Married . | Single . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative parenting | 54.38 | 24.54 | 288.50 | −4.61*** |

| Overinvolved parenting | 42.87 | 59.57 | 516.00 | −2.58* |

| Quality of life | 43.84 | 56.63 | 583.50 | −1.97* |

| HbA1c | 44.16 | 55.65 | 606.00 | −1.77 |

| Internalizing problems | 43.64 | 52.98 | 621.50 | −1.47 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.79 | 55.50 | 563.50 | −2.00* |

| . | Married . | Single . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative parenting | 54.38 | 24.54 | 288.50 | −4.61*** |

| Overinvolved parenting | 42.87 | 59.57 | 516.00 | −2.58* |

| Quality of life | 43.84 | 56.63 | 583.50 | −1.97* |

| HbA1c | 44.16 | 55.65 | 606.00 | −1.77 |

| Internalizing problems | 43.64 | 52.98 | 621.50 | −1.47 |

| Externalizing problems | 42.79 | 55.50 | 563.50 | −2.00* |

Note. *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Multiple regression analyses were used to examine the association of race/ethnicity and marital status with parenting behaviors, after adjusting for income and maternal education. The results of the first regression indicated that the model explained 15% of the variance in overinvolved parenting [R2 = .15, F(4, 60) = 2.53, p = .05]. The only significant predictor was race/ethnicity (β = −.29, p = .05). The results of the second regression indicated that the model explained 30% of the variance in collaborative parenting [R2 = .30, F(4, 60) = 6.29, p < .001]. In the final model, maternal education was a significant predictor (β = .32, p = .011), as well as marital status (β = .38, p = .011).

Differences in Adolescent Adjustment Related to Race/Ethnicity and Marital Status

As seen in Table II, the adolescent children of non-White mothers had significantly higher HbA1c and greater externalizing problems than adolescents of White mothers. There were no significant racial/ethnic differences in internalizing problems or quality of life. In addition, the adolescent children of single mothers reported more problems with quality of life and greater externalizing problems than the adolescent children of married mothers. There were no significant differences in glycemic control or quality of life related to marital status.

Associations Between Observed Parenting and Adolescent Adjustment

Bivariate correlations between observed parenting and adolescent adjustment (Table III) revealed that mothers’ higher levels of observed collaborative parenting were related to significantly lower levels of externalizing problems in adolescents (r = −.24, p = .021) and somewhat fewer problems with quality of life (r = −.19, p = .074). In contrast, overinvolved parenting was related to significantly higher levels of externalizing problems (r = .24, p = .020) and somewhat higher levels of internalizing problems (r = .18, p < .091). Observed parenting was not significantly associated with glycemic control.

Correlations Between Observed Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Adjustment Variables

| . | 1. . | 2. . | 3. . | 4. . | 5. . | 6. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Collaborative parenting | – | |||||

| M = 17.47 (3.75) | ||||||

| 2. Overinvolved parenting | .43*** | – | ||||

| M = 11.10 (4.10) | ||||||

| 3. Internalizing problems | −.10 | .18+ | – | |||

| M = −.01 (1.59) | ||||||

| 4. Externalizing problems | −.24* | .24* | .62*** | – | ||

| M = .01 (1.77) | ||||||

| 5. PedsQL | −.19+ | .13 | .58*** | .34*** | – | |

| M = 29.96 (14.70) | ||||||

| 6. A1C | −.15 | .17 | .22* | .20+ | .10 | – |

| M = 7.62 (1.15) |

| . | 1. . | 2. . | 3. . | 4. . | 5. . | 6. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Collaborative parenting | – | |||||

| M = 17.47 (3.75) | ||||||

| 2. Overinvolved parenting | .43*** | – | ||||

| M = 11.10 (4.10) | ||||||

| 3. Internalizing problems | −.10 | .18+ | – | |||

| M = −.01 (1.59) | ||||||

| 4. Externalizing problems | −.24* | .24* | .62*** | – | ||

| M = .01 (1.77) | ||||||

| 5. PedsQL | −.19+ | .13 | .58*** | .34*** | – | |

| M = 29.96 (14.70) | ||||||

| 6. A1C | −.15 | .17 | .22* | .20+ | .10 | – |

| M = 7.62 (1.15) |

Note. *p < . 05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Internalizing and externalizing are composite variables from the summed z-scores of the Child Behavior Checklist and Youth Self-Report.

PedsQL = Diabetes-Specific Pediatric Quality of Life.

Correlations Between Observed Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Adjustment Variables

| . | 1. . | 2. . | 3. . | 4. . | 5. . | 6. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Collaborative parenting | – | |||||

| M = 17.47 (3.75) | ||||||

| 2. Overinvolved parenting | .43*** | – | ||||

| M = 11.10 (4.10) | ||||||

| 3. Internalizing problems | −.10 | .18+ | – | |||

| M = −.01 (1.59) | ||||||

| 4. Externalizing problems | −.24* | .24* | .62*** | – | ||

| M = .01 (1.77) | ||||||

| 5. PedsQL | −.19+ | .13 | .58*** | .34*** | – | |

| M = 29.96 (14.70) | ||||||

| 6. A1C | −.15 | .17 | .22* | .20+ | .10 | – |

| M = 7.62 (1.15) |

| . | 1. . | 2. . | 3. . | 4. . | 5. . | 6. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Collaborative parenting | – | |||||

| M = 17.47 (3.75) | ||||||

| 2. Overinvolved parenting | .43*** | – | ||||

| M = 11.10 (4.10) | ||||||

| 3. Internalizing problems | −.10 | .18+ | – | |||

| M = −.01 (1.59) | ||||||

| 4. Externalizing problems | −.24* | .24* | .62*** | – | ||

| M = .01 (1.77) | ||||||

| 5. PedsQL | −.19+ | .13 | .58*** | .34*** | – | |

| M = 29.96 (14.70) | ||||||

| 6. A1C | −.15 | .17 | .22* | .20+ | .10 | – |

| M = 7.62 (1.15) |

Note. *p < . 05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Internalizing and externalizing are composite variables from the summed z-scores of the Child Behavior Checklist and Youth Self-Report.

PedsQL = Diabetes-Specific Pediatric Quality of Life.

Indirect Effect of Marital Status on Adolescent Adjustment

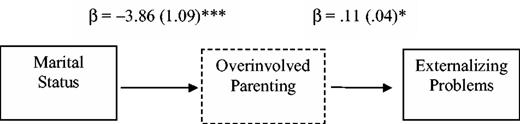

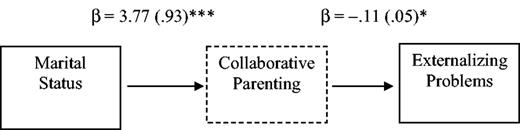

Following the statistical guidelines of MacKinnon and colleagues (2002), collaborative parenting and overinvolved parenting met the conditions as possible mediators for the effect of marital status on externalizing problems. Linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the regression coefficients (standardized B) and standardized error for each of the proposed pathways, adjusting for maternal education and annual household income. As seen in Figure 1, the indirect effect of marital status on externalizing problems through overinvolved parenting was significant, with a 95% CI of −.88 to −.06. Similarly, the indirect effect of marital status through collaborative parenting (Figure 2) was also significant, with a 95% CI of −.90 to −.06.

Overinvolved parenting as a mediator of marital status and adolescent externalizing problems. Unstandardized coefficients estimates and standard errors are presented for each step in this pathway (p < .05).

Collaborative parenting as a mediator of marital status and adolescent externalizing problems. Unstandardized coefficients estimates and standard errors are presented and for each step in this pathway (p < .05).

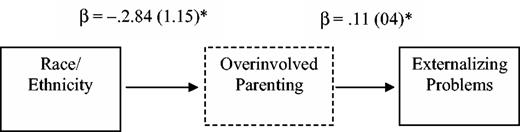

Indirect Effect of Race/Ethnicity on Adolescent Adjustment

Collaborative parenting and overinvolved parenting also met the conditions as possible mediators for the effect of race/ethnicity on externalizing problems. As seen in Figure 3, the indirect effect of race/ethnicity on externalizing problems through overinvolved parenting, adjusting for maternal education and income, was significant, with a 95% CI of −.71 to −.02. The indirect effect of race/ethnicity on externalizing problems through collaborative parenting was not significant (CI = −.33 to .19).

Overinvolved parenting as a mediator of race/ethnicity and adolescent externalizing problems. Unstandardized coefficients estimates and standard errors are presented for each step in this pathway, adjusting for maternal education and household income. *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to examine the relationship between demographic differences (i.e., race/ethnicity and marital status) and observed parenting behaviors, adolescent adjustment, and glycemic control in the context of T1D. The results from the present study suggest that key parenting behaviors differ by maternal demographics, and that these parenting behaviors have significant associations with adolescent adjustment. Thus, parenting may be one important pathway by which race/ethnicity and marital status influence adjustment in adolescents with T1D.

In line with the existing literature on demographic differences in parenting, our results indicate that parenting behaviors differed by marital status (Levine et al., 2001). As hypothesized, single/divorced mothers exhibited significantly less collaborative parenting behaviors than married/partnered mothers. This finding could represent an increased perception of stress experienced by single parents (Brown et al., 2008; Streisand, Mackey, & Herge, 2010; Thompson et al., 2001), which may be manifested in a maladaptive communication style to their children. Further, marital status was significantly associated with externalizing problems and quality of life in adolescents. Contrary to our hypothesis, however, there was not an effect of marital status on glycemic control or internalizing problems. We also found differences in parenting related to race/ethnicity, with minority mothers exhibiting higher levels of overinvolved parenting than White mothers. Consistent with previous findings, adolescent children of minority (non-White) mothers had significantly higher HbA1c compared with those of White mothers in our sample. However, we found no significant demographic differences in adolescents’ internalizing problems or quality of life. We may have been underpowered to detect differences in these variables between these groups, given that our sample reported relatively few problems with quality of life or behavior.

It is important to note that many of the demographic factors were confounded in our sample (e.g., 64% of the non-White mothers in our sample were single), and it is therefore difficult to tease out the effects of race/ethnicity and marital status on parenting behaviors and adolescent adjustment. In line with other research, poor glycemic control in minority youth could be explained by living in a single-parent household (Frey et al., 2007). In our multivariate analyses, we found that race/ethnicity was significantly associated with overinvolved parenting, while marital status and maternal education were significantly associated with collaborative parenting. These findings suggest that race/ethnicity may be a risk factor for more negative or intrusive involvement by parents, whereas maternal education may serve as a protective factor for more positive collaborative involvement. Income was not significantly associated with observed parenting in our sample. Although youth living in single-parent households are likely to have lower household income than youth in two-parent households, the effects of family structure may outweigh the effects of income on diabetes outcomes (Swift, Chen, Hershberger, & Holmes, 2006).

As hypothesized, parenting behaviors were significantly associated with adolescent adjustment in our sample. Specifically, higher levels of overinvolved parenting behaviors and lower levels of collaborative parenting behaviors were related to increased externalizing behavior problems in adolescents. This is in line with previous findings using questionnaire data that related positive and negative parenting behaviors to externalizing problems in adolescence (Reitz, Dekovic, & Meijer, 2006). Externalizing problems have been linked with poorer glycemic control and treatment adherence in youth with T1D (Cohen, Lumley, Naar-King, Partridge, & Cakan, 2004; Horton et al., 2009), and are therefore important to consider in the context of diabetes management. Finally, when examining parenting behaviors as a mediator of marital status and adolescent adjustment, both overinvolved parenting and collaborative parenting were significant mediators of externalizing problems in adolescents, and collaborative parenting was a mediator of the effect of race/ethnicity on externalizing problems. This finding is in line with recent conceptualizations that parenting may be particularly influential for externalizing problems in youth (Simons & Conger, 2007). There was not a significant association, however, between observed parenting behaviors and internalizing problems, quality of life, or glycemic control. As noted above, the lack of findings could be due to the relatively high quality of life and good glycemic control in our sample—with the majority meeting targets for glycemic control—limiting our ability to detect differences in these outcomes.

Limitations

The current study is limited by the small percentage of minority families in our sample; there was not enough diversity to examine differences in specific racial or ethnic groups, or to identify parenting differences related to specific racial/ethnic groups. For example, differences may exist within Hispanic parents, e.g., Mexican American youth report significantly lower levels of behavioral control (similar to intrusive parenting) than Central American youth (Chao & Kanatsu, 2008). As noted above, there was also significant overlap in our sample, such that non-White mothers were more likely to be single than married. In addition, our sample was fairly high functioning, so these results may not generalize to lower income adolescents or those with poorly controlled diabetes. The relatively low rate of participation (40%), which was likely due to the requirement of an extra visit to the laboratory, may also limit generalizability. Finally, it should be noted that the relationship between adolescent adjustment and parenting is likely to be bidirectional, and the cross-sectional nature of the current study does not allow us to test the direction of effects.

Implications

The present study replicates and extends previous research by examining race/ethnicity, marital status, and observed parenting in relation to both psychosocial and physiological indicators of adolescent adjustment. As previously demonstrated, minority adolescents and those from single-parent homes were at an elevated risk of poor glycemic control and adjustment problems. Given the shift over the past decades toward more single-parent households, especially in minority families (Vespa, Lewis, & Kreider, 2013), providers and researchers need to address parenting in this high-risk population. Previous family-based interventions have demonstrated that increased positive communication was associated with improvements in diabetes treatment adherence (Wysocki et al., 2008). Our results suggest that encouraging parents to use collaborative parenting, such as positive reinforcement, attentive listening, and soliciting adolescents’ opinions, may reduce risk for adjustment problems. While future studies should examine other possible mediators, the present study provides additional evidence that targeting improvements in collaborative parenting behaviors and reducing overinvolved or intrusive parenting strategies—especially in single and minority mothers—may lead to decreases in child externalizing problems in adolescents with T1D.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Benjamin Saville, PhD, for his statistical consultation.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23 NK088454) and the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR024139). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

1 There were outliers for two of the key variables (HbA1C, externalizing problems), but when we conducted a multivariate outlier analysis (using Mahalanobis distance to determine if any individual was an outlier on multiple variables), none was significant.