Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We investigated the association of early serum fatty acid composition with the risk of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. Our hypothesis was that fatty acid status during infancy is related to type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity and that long-chain n-3 fatty acids, in particular, are associated with decreased risk.

Methods

We performed a nested case–control analysis within the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Study birth cohort, carrying HLA-conferred susceptibility to type 1 diabetes (n = 7782). Serum total fatty acid composition was analysed by gas chromatography in 240 infants with islet autoimmunity and 480 control infants at the age of 3 and 6 months. Islet autoimmunity was defined as repeated positivity for islet cell autoantibodies in combination with at least one of three selected autoantibodies. In addition, a subset of 43 infants with primary insulin autoimmunity (i.e. those with insulin autoantibodies as the first autoantibody with no concomitant other autoantibodies) and a control group (n = 86) were analysed. A third endpoint was primary GAD autoimmunity defined as GAD autoantibody appearing as the first antibody without other concomitant autoantibodies (22 infants with GAD autoimmunity; 42 infants in control group). Conditional logistic regression was applied, considering multiple comparisons by false discovery rate <0.05.

Results

Serum fatty acid composition differed between breastfed and non-breastfed infants, reflecting differences in the fatty acid composition of the milk. Fatty acids were associated with islet autoimmunity (higher serum pentadecanoic, palmitic, palmitoleic and docosahexaenoic acids decreased risk; higher arachidonic:docosahexaenoic and n-6:n-3 acid ratios increased risk). Furthermore, fatty acids were associated with primary insulin autoimmunity, these associations being stronger (higher palmitoleic acid, cis-vaccenic, arachidonic, docosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids decreased risk; higher α-linoleic acid and arachidonic:docosahexaenoic and n-6:n-3 acid ratios increased risk). Moreover, the quantity of breast milk consumed per day was inversely associated with primary insulin autoimmunity, while the quantity of cow’s milk consumed per day was directly associated.

Conclusions/interpretation

Fatty acid status may play a role in the development of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. Fish-derived fatty acids may be protective, particularly during infancy. Furthermore, fatty acids consumed during breastfeeding may provide protection against type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. Further studies are warranted to clarify the independent role of fatty acids in the development of type 1 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease characterised by the destruction of pancreatic beta cells. Inflammatory reactions and immunological dysfunction precede the disease [1, 2], often beginning in infancy or early childhood [3]. Fatty acids may play a role in the development of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity, as they have been shown to modulate the immune system and inflammatory reactions [4, 5]. Furthermore, early fatty acid status may be important because it can affect programming and development of an infant’s immune system, as well as the maturation of the gut, with long-term consequences [6, 7]. Other lipids could also play a role. Interestingly, early lipidomic profile was associated with progression to type 1 diabetes [8]. Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) intake and/or status were protectively related to type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity or clinical disease in several [9,10,11], but not all [12, 13], epidemiological studies. Maternal intake and status of fish-derived fatty acids during pregnancy were not associated with the risk of developing type 1 diabetes in the offspring [9, 14, 15], with the exception of one case–control study reporting a protective association [16]. Saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) have also been associated with the risk of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. In the Finnish type 1 diabetes prediction and prevention (DIPP) study, high serum levels of cow’s milk-derived fatty acids were associated with a higher risk of islet autoimmunity [12]. This is in line with the observed association between milk fat consumption and increased risk of islet autoimmunity [17].

During early infancy, breast milk and infant formulas are the main dietary sources of fatty acids and therefore the type of milk feeding is likely the most important determinant of fatty acid status. Breastfeeding, measured as breastfeeding duration, was not found to be associated with the risk of islet autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes in cohort studies [17,18,19,20]. Looking at the other side of the coin, cow’s milk consumption (measured as the quantity consumed) during infancy and childhood was related to increased risk of islet autoimmunity and/or type 1 diabetes in several prospective cohort series [17, 21,22,23,24]. The cause is unknown and several components in milk may be involved [25,26,27].

Our hypothesis was that fatty acid status during infancy is related to type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity and that, in particular, high levels of long-chain n-3 PUFAs are associated with decreased risk.

Methods

Study design

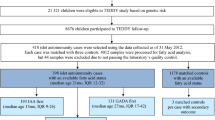

The study was carried out in a nested case–control design within the Finnish DIPP Nutrition Study and included children at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes (n = 7782). Increased genetic risk was determined by the presence in cord blood of a high-risk genotype (HLA-DQB1*02:*0302) or a moderate-risk genotype (HLA-DQB1*0302:x, where x = other than *02, *0301 or *0602). Children were recruited during the years 1997 and 2004. Informed consent was obtained from the families. DIPP children are monitored for islet autoimmunity and their blood samples are collected by venepuncture at the ages of 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months and subsequently at 12 month intervals up to the age of 15 years. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the local ethics committees.

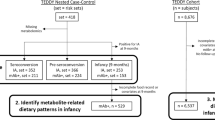

For the nested case–control design, all cases of islet autoimmunity and of type 1 diabetes without preceding islet autoimmunity were identified at the end of the follow-up period (Fig. 1). The participants were monitored for the appearance of markers for islet autoimmunity and clinical type 1 diabetes. Islet cell autoantibodies (ICA) were used as the primary screening tool for beta cell autoimmunity. When a child seroconverted to positivity for ICA for the first time, all that child’s preceding and subsequent samples were analysed for insulin autoantibodies (IAA), autoantibodies to 65 kDa isoform of GAD (GADA) and antibodies to tyrosine phosphatase-related islet antigen 2 (IA-2A) and at this point the follow-up interval was shortened to 3 months.

Flow chart of the study. Islet autoimmunity was defined as repeated positivity for ICA in combination with at least one of the biochemical markers analysed (IAA, GADA or IA-2A) or presence of clinical type 1 diabetes. Primary insulin autoimmunity was defined as IAA appearing as the first autoantibody without any other concomitant autoantibodies. Primary GAD autoimmunity was defined as being first positive only for GADA out of the four autoantibodies measured (ICA, IAA, GADA, IA-2A). T1D, type 1 diabetes

Autoantibody assays

ICA were quantified by a standard indirect immunofluorescence method on sections of frozen human pancreas from a blood group O donor [28]. IAA were quantified by microassay [29, 30] and GADA and IA-2A were analysed using specific radiobinding assays [31,32,33]. Details of the autoantibody methods are described by Kimpimäki et al [34].

Definition of outcomes

Islet autoimmunity was defined as repeated positivity for ICA in combination with at least one of the biochemical autoantibodies analysed (IAA, GADA or IA-2A), or the presence of clinical type 1 diabetes. The median age of islet autoimmunity endpoint was 3.0 years (range 0.5–9.2). The diagnosis of diabetes was based on the WHO criteria. As a second endpoint within our islet autoimmunity case children, we used primary insulin autoimmunity, defined as IAA appearing as the first antibody without any other concomitant autoantibodies. The median age of primary insulin autoimmunity was 1.0 years (range 0.2–4.2). As a third endpoint, we used primary GAD autoimmunity in children with islet autoimmunity. Primary GAD autoimmunity was defined as GADA appearing as the first antibody without other concomitant autoantibodies. The median age of primary GAD autoimmunity was 2.0 years (range 0.2–7.1). Distributions of seroconversion age for islet autoimmunity, primary insulin autoimmunity and GAD autoimmunity are presented in Table 1.

Selection of controls

Matching criteria for the control children were the same sex, HLA-conferred DQB1 risk group (moderate or high risk), delivery hospital, the date of birth within 3 months in relation to the case children and not being from the same family as the case children. From all potential control children, two seronegative children were randomly selected at the age point at which the respective case child turned out to have islet autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes. For the random selection, one child could serve as a control for more than one case and could subsequently become a case. Thirty-one children served as control for two or more case children and ten of the control children later became a case. Finally, the total fatty acid composition was analysed in 240 children with islet autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes and 480 matched seronegative control children from the 3 and 6 month serum samples (Table 2).

Measurement of serum fatty acid status

Serum fatty acid proportions were determined by using a gas chromatographic method (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) as described earlier [12]. Each case–control set was analysed in the same batch. Laboratory staff were blinded for case–control status.

Assessment of the child’s diet

Dietary information was obtained at the age of 3 and 6 months by a 3 day food record (including two weekdays and one weekend day [17]) and a dietary questionnaire in which families recorded the infant’s age at introduction of new foods and breastfeeding. Infant feeding pattern, including feeding in the delivery hospital, was also established by interview during the clinical visits (3, 6, 9, 12 months). Families were given oral and written instructions by trained research nurses in how to fill in the food records, day care personnel were provided with written instructions and the records were checked by trained research nurses at the clinical visit [17].

Our definition of exclusive breastfeeding was that breast milk was the only drink or food to which the infant was exposed, except for water and dietary supplementation (not containing energy). The composition of breast milk was taken from the Finnish national food composition database (FINELI) which was updated based on Finnish breast milk samples collected during the years 2011–2012 from 40 women whose children were 1–6 months of age. Fatty acid composition of infant formula was based on data reported by the manufacturers.

Calculation of the quantity of breast milk consumed

The quantity of breast milk consumed was calculated using estimated energy requirements and growth [35]. The length and weight of the children were measured every 3 months during the first year of life at the study centre visits. Energy need was estimated based on energy requirements for weight and age, plus the estimated amount of incremental energy needed to support tissue accretion (energy deposition) [35]. Estimated energy requirement equalled total energy requirement plus energy deposition. Estimated energy from breast milk equalled estimated energy requirement minus energy intake from food records. Based on this, the quantity of breast milk consumed per day was calculated.

Statistical analyses

Background characteristics of children comprising cases and their controls were compared using conditional logistic regression analysis. This accounts for the matching of cases and controls and is the standard method of estimation in nested case–control study designs. To analyse the serum fatty acid status in breastfed and non-breastfed infants, they were categorised according to their breastfeeding status at the age of 3 months: (1) exclusively breastfed; (2) breastfed, but not exclusively breastfed and (3) non-breastfed. At the age of 6 months we used only two categories for breastfeeding: (1) breastfed and (2) non-breastfed. This was because there were only six children who were exclusively breastfed at that age. The differences in serum status between breastfeeding categories were tested using mixed linear model with matched sets used as random effects.

To assess the associations between serum fatty acid proportions and islet autoimmunity, primary insulin autoimmunity or primary GAD autoimmunity, conditional logistic regression was applied. To account for potential confounders, we included cow’s milk consumption, familial diabetes and maternal vocational education in the multiple conditional likelihood logistic regression models. We used cow’s milk consumption as an adjusting factor because it is a more accurate variable (measured by food records) than breastmilk consumption (estimate based on growth). The quantity of cow’s milk and breast milk consumed cannot be included as adjusting factors in the same model because of their strong correlation. Children with missing confounder data were excluded from the adjusted analysis. Multiple testing was addressed by using a p value adjustment method that controls the false discovery rate (FDR) [36].We considered FDR <0.05 to be significant. Interactions between fatty acids and breastfeeding with the endpoints were studied by adding an interaction term to the conditional logistic regression model. We reported results from the interaction models if there was an indication of an interaction (FDR <0.05). Spearman’s correlations between serum fatty acids and milk feeding were also calculated. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Background variables and the risk of islet autoimmunity

Familial type 1 diabetes was associated with an increased risk of islet autoimmunity, while maternal vocational education was associated with a decreased risk (Table 2).

Serum fatty acid status in relation to breastfeeding status

Serum fatty acid status differed between breastfed and non-breastfed infants at the ages of 3 months and 6 months, reflecting differences in fatty acid composition of breast milk and infant formulas (Table 3). Breastfed infants had higher serum levels of myristic, stearic, conjugated linoleic (CLA), palmitoleic, cis-vaccenic, dihomo-γ-linolenic (GLA), arachidonic (AA), eicosapentaenoic (EPA), docosapentaenoic (DPA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acids, compared with non-breastfed infants, at 3 and 6 months of age. Breastfed infants had lower serum levels of oleic, linoleic (LA) and GLA compared with non-breastfed infants. In addition, at the age of 3 months, the breastfed infants had a higher serum level of pentadecanoic acid compared with non-breastfed infants. At 6 months of age, breastfed infants had a lower serum level of α-linolenic acid (ALA) (Table 3). The ratios of n-6:n-3 fatty acids and AA:DHA in serum at 3 and 6 months were lower in breastfed infants than in non-breastfed infants (Table 3). These results are in line with lower contents of oleic acid, LA and ALA and higher content of myristic, pentadecanoic, stearic, palmitoleic, cis-vaccenic and dihomo-GLA and CLA, AA, EPA, DPA and DHA in breast milk than in infant formula (Table 3).

Fatty acids that were present at higher proportions in serum of breastfed infants and present at comparatively high proportions in breast milk correlated directly with the amount of breast milk consumed, and inversely with the amount of cow’s milk consumed, by control children at the age of 3 and/or 6 months (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). Respectively, fatty acids present at higher proportions in serum of non-breastfed infants, consumed in comparatively higher amounts in cow’s milk, correlated directly with the amounts of cow’s milk consumed and inversely with the amount of breast milk consumed (ESM Table 1).

Serum fatty acid status, type of milk feeding and the risk of islet autoimmunity

Higher serum levels of palmitic and palmitoleic acid (16:1n-9) at the age of 3 months, as well as pentadecanoic acid at the age of 6 months, were associated with a decreased risk of islet autoimmunity (Table 4). On the other hand, serum AA:DHA ratio at the age of 3 months and serum n-6:n-3 ratio at the age of 6 months was associated with an increased risk of islet autoimmunity. Breastfeeding status modified the associations between serum DHA and the risk of islet autoimmunity at the age of 3 months (p = 0.003, FDR = 0.024). The proportion of DHA in the serum was associated with a decreased risk of islet autoimmunity only in non-breastfed children (Table 4).

Serum fatty acid status, milk feeding and the risk of primary insulin autoimmunity

The proportions of palmitoleic acid, cis-vaccenic acid, AA, DPA and DHA were inversely associated with primary insulin autoimmunity at the age of 3 and/or 6 months (Table 5). ALA and high ratios of AA:DHA and n-6:n-3 were associated with increased risk. Higher breast milk consumption was associated with a decreased risk of primary insulin autoimmunity, whereas cow’s milk consumption was associated with an increased risk.

Serum fatty acid status, milk feeding and the risk of primary GAD autoimmunity

After multiple testing, fatty acid status in infancy was not associated with GAD autoimmunity (ESM Table 2).

Adjustments for background factors and milk feeding

Adjusting conditional logistic regression models for familial diabetes and maternal education did not change the results (data not shown). Adjusting for cow’s milk consumption did not change the association between fatty acids and islet autoimmunity substantially (ESM Fig. 1). Although this adjustment diluted the associations between SFAs and MUFAs and primary insulin autoimmunity, the associations between fish-derived fatty acids and primary insulin autoimmunity remained essentially unchanged (ESM Fig. 1). After correction for multiple testing, the results were non-significant (FDR <0.05).

Discussion

Main findings

Fatty acid status in infancy was related to type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. Fish-derived fatty acids in particular appeared to be protective. In addition, fatty acids found in breast milk were protectively associated with islet autoimmunity and primary insulin autoimmunity. Generally, associations were stronger for primary insulin autoimmunity, the earliest endpoint investigated, compared with later.

Strengths

Our study used a nested case–control design within a well-defined prospective birth cohort and had a comparatively large number of islet autoimmunity endpoints. Furthermore, established and well-functioning biomarkers were used; an earlier validation study from DIPP, comparing food consumption data with serum fatty acid composition, showed that fatty acid proportions in non-fasting, whole serum are suitable biomarkers in young children [37]. Importantly, the current study was performed at a time when DHA was not yet added to infant formulas in Finland and therefore its intake was low in formula-fed infants. This created a relatively large contrast in exposure, which is an advantage. Moreover, we investigated dietary factors in infancy and it is important to note that estimation of an infant’s diet is comparatively easy and accurate because it is less variable than that of an older child.

Limitations

Fatty acids found in the peripheral circulation of infants originate from infant and maternal diets and adipose tissue storage, as well as metabolic processes, some of which are affected by genetic factors [38, 39]. It can be considered a limitation that it was not possible to account for genetic factors involved in fatty acid metabolism. Furthermore, the study included a relatively low number of cases with primary insulin autoimmunity (n = 43) and primary GAD autoimmunity (n = 22) compared with the islet autoimmunity endpoint (n = 240). Thus, the statistical power may have been insufficient to show statistically significant associations between fatty acid proportions and the primary GAD endpoint, particularly, after multiple testing (FDR <0.05).

n-3 PUFAs and risk of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity

Fish-derived fatty acids DHA and DPA were associated with decreased risk of primary insulin autoimmunity. For islet autoimmunity, a protective association was observed in non-breastfed infants at 3 months of age. Overall, these results suggest that long-chain n-3 PUFAs are protective during infancy. We reported earlier that long-chain n-3 PUFA proportions were not associated with islet autoimmunity in older children (1–6 years of age) in the DIPP cohort [12]. Altogether, the results indicate that long-chain n-3 PUFA status during the early months, a time when the immune system is maturing and being programmed, is critical.

Interestingly, a very strong association was found between DHA and decreased risk of islet autoimmunity in non-breastfed infants. These infants had the lowest levels of long-chain n-3 PUFAs because very few consumed fish and DHA was not present in formula at that time. This indicates an independent role for long-chain n-3 fatty acids in the development of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. It should be noted that this result is not confounded by breastfeeding.

Only 19% of the infants in the DIPP cohort had eaten fish by the age of 6 months and therefore the source of EPA, DPA and DHA was maternal diet (during pregnancy or lactation) or endogenous synthesis from their precursor ALA. ALA per se was associated with increased risk of primary insulin autoimmunity, which is in line with our earlier observation that maternal consumption of vegetable oils during lactation was associated with increased risk of islet autoimmunity in this cohort [40]. ALA in the maternal diet comes mainly from vegetable oils; in 3-month-old infants it is obtained from breast milk and formula. The ratios of n-6:n-3 and AA:DHA were associated with increased risk of islet autoimmunity and primary insulin autoimmunity. This may reflect the beneficial effect of long-chain n-3 fatty acids.

Our results concerning long-chain n-3 PUFAs are in line with the findings of a Norwegian case–control study suggesting that the use of cod liver oil (rich in EPA and DHA) during the first year of life protects against type 1 diabetes [9]. Furthermore, the prospective Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY), investigating older children (9 months to 8 years of age), found that high dietary intake and erythrocyte membrane content of n-3 PUFAs were associated with a decreased risk of islet autoimmunity (defined as repeated positivity for at least one autoantibody) [10, 11], but not with progression to type 1 diabetes [13]. Results from DAISY as well as the DIPP cohort support the view that early stages of autoimmunity are affected by long-chain n-3 PUFAs.

Fatty acids related to breast milk and risk of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity

Fatty acids present in higher quantities in breast milk, as well as serum of breastfed infants (pentadecanoic, palmitic, palmitoleic and cis-vaccenic acids and AA, DPA and DHA), were associated with decreased risk of islet autoimmunity or primary insulin autoimmunity, or both. Furthermore, the quantity of breast milk consumed was associated with decreased risk of primary insulin autoimmunity. The findings support the view that breastfeeding or some components of breast milk, including fatty acids, are protective, particularly against early autoimmunity. As far as we know, our study is the first one investigating the amount of breast milk consumed in this context, and having primary insulin and GAD autoimmunity as outcomes. Earlier findings on the associations between duration of breastfeeding and risk of developing type 1 diabetes are inconsistent. Most prospective cohort studies do not show any association between breastfeeding duration and the risk of islet autoimmunity or type 1 diabetes [18,19,20] apart from a Swedish study that reported a protective association with islet autoimmunity [23] and a Norwegian study that reported a protective association for progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes [41].

In our study, the quantity of cow’s milk consumed was associated with an increased risk of primary insulin autoimmunity. Our findings are in line with previous prospective cohort studies on milk consumption during infancy and childhood and the development of islet autoimmunity and/or type 1 diabetes [17, 21,22,23,24].

Cow’s milk as adjusting factor

To investigate whether fatty acids are independently associated with type 1 diabetes autoimmunity, and not merely a reflection of the type of milk consumed, we adjusted the statistical models for the amount of cow’s milk consumed. This did not substantially change results, suggesting that fatty acid status is indeed independently associated with islet autoimmunity. For primary insulin autoimmunity, as expected, most of the associations were diluted, because of the strong association between milk type and primary insulin autoimmunity (applied to SFA, MUFA, ratios of AA:DHA and n-6:n-3).

Differences between endpoints

We observed stronger associations for primary insulin autoimmunity, the earliest endpoint investigated, compared with the later endpoints (islet autoimmunity and primary GAD). First, the explanation for why different associations are seen for different endpoints may be that their development differs by genotype and therefore the pathogenic processes may be different [42]. Second, measurements of fatty acid status and primary insulin autoimmunity are carried out within a short period and therefore there may be less confounding. It is possible that a protective association is more difficult to demonstrate at a later age, because the diet becomes more variable.

Conclusions

Our results show that fatty acid status in infants strongly reflects the type of milk feeding. Higher proportions of fish-derived fatty acids as well as fatty acids related to breastfeeding may provide protection from type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. Furthermore, breast milk consumption may reduce, and cow’s milk consumption may increase, the risk of primary insulin autoimmunity. This study clarifies the complex associations between fatty acid status, milk type and type 1 diabetes development, but further studies on the subject are warranted.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Arachidonic acid

- ALA:

-

α-Linolenic acid

- CLA:

-

Conjugated linoleic acid

- DIPP:

-

Type 1 diabetes prediction and prevention study

- DHA:

-

Docosahexaenoic acid

- DPA:

-

Docosapentaenoic acid

- EPA:

-

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- GADA:

-

Autoantibodies to 65 kDa isoform of GAD

- GLA:

-

γ-Linolenic acid

- IAA:

-

Insulin autoantibodies

- IA-2A:

-

Antibodies to tyrosine phosphatase-related islet antigen 2

- ICA:

-

Islet cell autoantibodies

- LA:

-

Linoleic acid

- MUFA:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- SFA:

-

Saturated fatty acid

References

Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW (2014) Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 383:69–82

Zipris D (2013) The interplay between the gut microbiota and the immune system in the mechanism of type 1 diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 20:265–270

Vehik K, Lynch KF, Schatz DA et al (2016) Reversion of β-cell autoimmunity changes risk of type 1 diabetes: TEDDY Study. Diabetes Care 39:1535–1542

Calder PC (2013) N-3 fatty acids, inflammation and immunity: new mechanisms to explain old actions. Proc Nutr Soc 72:326–336

Galli C, Calder PC (2009) Effects of fat and fatty acid intake on inflammatory and immune responses: a critical review. Ann Nutr Metab 55:123–139

Innis SM (2011) Metabolic programming of long-term outcomes due to fatty acid nutrition in early life. Matern Child Nutr 7(Suppl 2):112–123

Nauta AJ, Ben Amor K, Knol J, Garssen J, van der Beek EM (2013) Relevance of pre- and postnatal nutrition to development and interplay between the microbiota and metabolic and immune systems. Am J Clin Nutr 98:586S–593S

Oresic M, Gopalacharyulu P, Mykkanen J et al (2013) Cord serum lipidome in prediction of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 62:3268–3274

Stene LC, Joner G, Norwegian Childhood Diabetes Study Group (2003) Use of cod liver oil during the first year of life is associated with lower risk of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: a large, population-based, case-control study. Am J Clin Nutr 78:1128–1134

Norris JM, Yin X, Lamb MM et al (2007) Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and islet autoimmunity in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes. JAMA 298:1420–1428

Norris JM, Kroehl M, Fingerlin TE et al (2014) Erythrocyte membrane docosapentaenoic acid levels are associated with islet autoimmunity: the diabetes autoimmunity study in the young. Diabetologia 57:295–304

Virtanen SM, Niinisto S, Nevalainen J et al (2010) Serum fatty acids and risk of advanced β-cell autoimmunity: a nested case-control study among children with HLA-conferred susceptibility to type I diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr 64:792–799

Miller MR, Yin X, Seifert J, Clare-Salzler M et al (2011) Erythrocyte membrane omega-3 fatty acid levels and omega-3 fatty acid intake are not associated with conversion to type 1 diabetes in children with islet autoimmunity: the diabetes autoimmunity study in the young (DAISY). Pediatr Diabetes 12:669–675

Sorensen IM, Joner G, Jenum PA, Eskild A, Stene LC (2012) Serum long chain n-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) in the pregnant mother are independent of risk of type 1 diabetes in the offspring. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 28:431–438

Niinisto S, Takkinen HM, Uusitalo L et al (2014) Maternal dietary fatty acid intake during pregnancy and the risk of preclinical and clinical type 1 diabetes in the offspring. Br J Nutr 111:895–903

Stene LC, Ulriksen J, Magnus P, Joner G (2000) Use of cod liver oil during pregnancy associated with lower risk of type I diabetes in the offspring. Diabetologia 43:1093–1098

Virtanen SM, Nevalainen J, Kronberg-Kippila C et al (2012) Food consumption and advanced beta cell autoimmunity in young children with HLA-conferred susceptibility to type 1 diabetes: a nested case-control design. Am J Clin Nutr 95:471–478

Norris JM, Barriga K, Klingensmith G et al (2003) Timing of initial cereal exposure in infancy and risk of islet autoimmunity. JAMA 290:1713–1720

Ziegler AG, Schmid S, Huber D, Hummel M, Bonifacio E (2003) Early infant feeding and risk of developing type 1 diabetes-associated autoantibodies. JAMA 290:1721–1728

Virtanen SM, Takkinen HM, Nevalainen J, Kronberg-Kippila C et al (2011) Early introduction of root vegetables in infancy associated with advanced ss-cell autoimmunity in young children with human leukocyte antigen-conferred susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 28:965–971

Virtanen SM, Hypponen E, Laara E et al (1998) Cowʼs milk consumption, disease-associated autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes mellitus: a follow-up study in siblings of diabetic children. Childhood diabetes in Finland study group. Diabet Med 15:730–738

Virtanen SM, Laara E, Hypponen E et al (2000) Cow’s milk consumption, HLA-DQB1 genotype, and type 1 diabetes: a nested case-control study of siblings of children with diabetes. Childhood diabetes in Finland study group. Diabetes 49:912–917

Wahlberg J, Vaarala O, Ludvigsson J, ABIS-study group (2006) Dietary risk factors for the emergence of type 1 diabetes-related autoantibodies in 21/2 year-old Swedish children. Br J Nutr 95:603–608

Lamb MM, Miller M, Seifert JA et al (2015) The effect of childhood cowʼs milk intake and HLA-DR genotype on risk of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: the diabetes autoimmunity study in the young. Pediatr Diabetes 16:31–38

Knip M, Virtanen SM, Seppa K et al (2010) Dietary intervention in infancy and later signs of beta-cell autoimmunity. N Engl J Med 363:1900–1908

Knip M, Akerblom HK, Becker D et al (2014) Hydrolyzed infant formula and early β-cell autoimmunity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311:2279–2287

Vaarala O, Ilonen J, Ruohtula T et al (2012) Removal of bovine insulin from cowʼs milk formula and early initiation of beta-cell autoimmunity in the FINDIA pilot study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166:608–614

Bottazzo GF, Florin-Christensen A, Doniach D (1974) Islet-cell antibodies in diabetes mellitus with autoimmune polyendocrine deficiencies. Lancet 2:1279–1283

Williams AJ, Bingley PJ, Bonifacio E, Palmer JP, Gale EA (1997) A novel micro-assay for insulin autoantibodies. J Autoimmun 10:473–478

Ronkainen MS, Hamalainen AM, Koskela P, Akerblom HK, Knip M, Finnish Trigr Study Group (2001) Pregnancy induces nonimmunoglobulin insulin-binding activity in both maternal and cord blood serum. Clin Exp Immunol 124:190–196

Petersen JS, Hejnaes KR, Moody A et al (1994) Detection of GAD65 antibodies in diabetes and other autoimmune diseases using a simple radioligand assay. Diabetes 43:459–467

Savola K, Sabbah E, Kulmala P, Vahasalo P, Ilonen J, Knip M (1998) Autoantibodies associated with type I diabetes mellitus persist after diagnosis in children. Diabetologia 41:1293–1297

Savola K, Bonifacio E, Sabbah E et al (1998) IA-2 antibodies—a sensitive marker of IDDM with clinical onset in childhood and adolescence. Childhood diabetes in Finland study group. Diabetologia 41:424–429

Kimpimaki T, Kulmala P, Savola K et al (2000) Disease-associated autoantibodies as surrogate markers of type 1 diabetes in young children at increased genetic risk. Childhood diabetes in Finland study group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:1126–1132

Schoen S, Sichert-Hellert W, Kersting M (2009) Validation of energy requirement equations for estimation of breast milk consumption in infants. Public Health Nutr 12:2309–2316

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc 57:289–300

Uusitalo L, Nevalainen J, Salminen I et al (2013) Fatty acids in serum and diet--a canonical correlation analysis among toddlers. Matern Child Nutr 9:381–395

Schaeffer L, Gohlke H, Muller M et al (2006) Common genetic variants of the FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster and their reconstructed haplotypes are associated with the fatty acid composition in phospholipids. Hum Mol Genet 15:1745–1756

Standl M, Lattka E, Stach B et al (2012) FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster. PUFA intake and blood lipids in children: results from the GINIplus and LISAplus studies PLoS One 7:e37780

Niinisto S, Takkinen HM, Uusitalo L et al (2015) Maternal intake of fatty acids and their food sources during lactation and the risk of preclinical and clinical type 1 diabetes in the offspring. Acta Diabetol 52:763–772

Lund-Blix NA, Stene LC, Rasmussen T, Torjesen PA, Andersen LF, Ronningen KS (2015) Infant feeding in relation to islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in genetically susceptible children: the MIDIA study. Diabetes Care 38:257–263

Ilonen J, Hammais A, Laine AP et al (2013) Patterns of beta-cell autoantibody appearance and genetic associations during the first years of life. Diabetes 62:3636–3640

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the children and parents who participated. We thank the DIPP research nurses, doctors, nutritionists and laboratory staff in the University Hospitals of Oulu and Tampere, Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Tampere and the Nutrition Unit in the National Institute for Health and Welfare for excellent collaboration over the years. I. Salminen (Public Health Solutions, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland) is gratefully acknowledged for scientific advice and assistance during fatty acid analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the protection of the identity of the study participants and their clinical data, but data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (Grants 63672, 68292, 79685, 79686, 80846, 114666, 126813, 129492, 139391, 201988, 210632, 276475), European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD/Novo Nordisk Partnership and EFSD/JDRF/Novo Nordisk Programme), the Juho Vainio Foundation, the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, the Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Tampere, Turku and Oulu University Hospitals (Grants 9E082, 9F089, 9G087, 9H092, 9J147, 9K149, 9L042, 9L117, 9M036, 9M114, 9N086, 9P057, 9R055, 9S074), the JDRF (grants 4-1998-274, 4-1999-731, 4-2001-435), the European Union (grant BMH4-CT98-3314), the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Academy of Finland (Centre of Excellence in Molecular Systems Immunology and Physiology Research 2012–2017, Decision No. 250114) and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation. The study sponsors were not involved in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

All authors were responsible for the study concept and design, acquisition of data and analysis or interpretation of the data. SN, IE, OV and SMV researched data. IE supervised serum fatty acid analyses. H-MT performed statistical analysis. SA supervised dietary data collection, processing and analysis. JT, RV and MK provided the clinical data used in this study and supervised the clinical work. RV and MK were responsible for the autoantibody analyses and JI for the genetic analyses. SN wrote the first version of the manuscript. IE contributed significantly to the writing and revision of the manuscript. SMV reviewed the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version to be published. SMV is the guarantor of this work and, as such had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niinistö, S., Takkinen, HM., Erlund, I. et al. Fatty acid status in infancy is associated with the risk of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. Diabetologia 60, 1223–1233 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-017-4280-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-017-4280-9